VIDEO (Click Link Below) – Putting Up The Flag

Putting Up The Flag

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Report of Ensign Joseph D. McGraw

Patrol Over Leyte

October 24, 1944

* * *

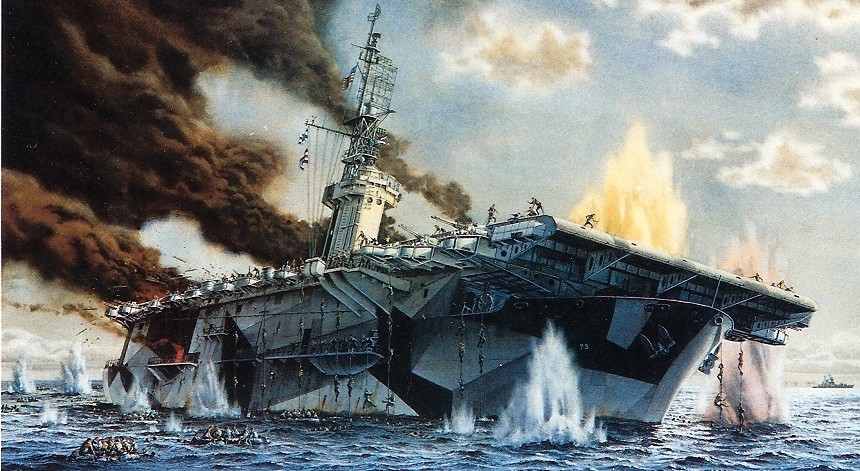

The painting below is by VC-10 fighter pilot Joseph McGraw.

The painting depicts the fifth enemy aircraft that he shot down

during the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Our VF division was catapulted at 0500. We joined up and departed from over the lead destroyer. We arrived on station at about 0525, and patrolled from Point KING to Point NAN. At about 0800 over point KING a large bogie was reported. We started climbing at full military power as we were only at about 4000’. We had been chasing a bogie on the deck which turned out to be a TBM. We tally hoed three SALLY’s high above us (about 12000’), and Lt. Seitz and Ens. Dugan, his wingman overtook two of them to shoot them down a few miles west of Tacloban Town. I was unable to close within firing range. I think the third SALLY was also shot down by a VC-10 fighter. During the chase I became separated from my section leader, so I joined up on Lt. Seitz. We circled at point KING again until Lt. Seitz was forced to leave due to shortage of fuel. I remained on station as I still had about 65 gallons. At about 0840 a large bogie was reported coming in at point KING, high. Just then a large formation of twin-engine bombers was tally hoed. I was at 10,000’, and a I climbed to 13,000’. I sighted about 21 LILLY’s in close formation headed for Leyte Gulf a 15,000’. I made my first run on a section of LILLY’s, low, and on the starboard side of the formation. I fired a long burst at mid-range of about 200 yards at the section leader from a full deflection down to about 30 degrees. My tracers were hitting the starboard side of the fuselage just aft of the cockpit, but he seemed to suffer no serious damage. Then I concentrated my fire at his wingman at about 100 yards range. After a long burst from 20 degree deflection to almost dead astern, that went into his starboard engine and wing root, the LILY burst into flames, and dropped out of the formation. Just as he fell, in flames, his starboard wing came off. Just as the LILY burst into flames another FM-2 zoomed very close underneath me-coming from my left. He may have been firing at the same LILY as I although I saw no other tracers. There was no return fire from this plane, although the dorsal hatch was opened. He made no evasive action-but held in formation. His speed was 160-170 knots, and mine was from 180-200 IAS. I recovered to the right of the bombers and made another beam run from the starboard,this time on a lone LILY low and on the starboard side of the formation. I fired a long burst from full deflection down to about 30 degrees, and observed hits on the fuselage and cockpit. I then sucked in behind and fired another long burst at his port engine,which exploded and caught fire. Then I fired into his port wing roots, which also flamed. As the LILY dropped off on his left wing, I rolled to the left. As I did the rear hatch gunner scored 8 hits on my plane, although none did any serious damage. The LILY continued its roll and spun-in in flames. I recovered on the left side of the remaining bombers, and I now saw only six left. I made two more runs on the rear LILLY’s but observed no real damage from my fire. Three more of the bombers were shot down by other fighters, two were in flames, before they arrived over the transports in the Gulf. As the remaining three bombers dove thru the thin layers of clouds over the ships, the ships’ AA opened fire. I pulled out to the left and headed back to point NAN. I observed two planes crash into the water that had probably been hit by our AA fire, and one was close alongside a large landing ship just off shore. At Point NAN I joined up with Lt. Seitz, who had turned back, and Lt. (jg) Hunting. Aswe were all quite low on fuel we headed for our base. I landed aboard with from 8-10 gallons at 0930.

Our VF division was catapulted at 0500. We joined up and departed from over the lead destroyer. We arrived on station at about 0525, and patrolled from Point KING to Point NAN. At about 0800 over point KING a large bogie was reported. We started climbing at full military power as we were only at about 4000’. We had been chasing a bogie on the deck which turned out to be a TBM. We tally hoed three SALLY’s high above us (about 12000’), and Lt. Seitz and Ens. Dugan, his wingman overtook two of them to shoot them down a few miles west of Tacloban Town. I was unable to close within firing range. I think the third SALLY was also shot down by a VC-10 fighter. During the chase I became separated from my section leader, so I joined up on Lt. Seitz. We circled at point KING again until Lt. Seitz was forced to leave due to shortage of fuel. I remained on station as I still had about 65 gallons. At about 0840 a large bogie was reported coming in at point KING, high. Just then a large formation of twin-engine bombers was tally hoed. I was at 10,000’, and a I climbed to 13,000’. I sighted about 21 LILLY’s in close formation headed for Leyte Gulf a 15,000’. I made my first run on a section of LILLY’s, low, and on the starboard side of the formation. I fired a long burst at mid-range of about 200 yards at the section leader from a full deflection down to about 30 degrees. My tracers were hitting the starboard side of the fuselage just aft of the cockpit, but he seemed to suffer no serious damage. Then I concentrated my fire at his wingman at about 100 yards range. After a long burst from 20 degree deflection to almost dead astern, that went into his starboard engine and wing root, the LILY burst into flames, and dropped out of the formation. Just as he fell, in flames, his starboard wing came off. Just as the LILY burst into flames another FM-2 zoomed very close underneath me-coming from my left. He may have been firing at the same LILY as I although I saw no other tracers. There was no return fire from this plane, although the dorsal hatch was opened. He made no evasive action-but held in formation. His speed was 160-170 knots, and mine was from 180-200 IAS. I recovered to the right of the bombers and made another beam run from the starboard,this time on a lone LILY low and on the starboard side of the formation. I fired a long burst from full deflection down to about 30 degrees, and observed hits on the fuselage and cockpit. I then sucked in behind and fired another long burst at his port engine,which exploded and caught fire. Then I fired into his port wing roots, which also flamed. As the LILY dropped off on his left wing, I rolled to the left. As I did the rear hatch gunner scored 8 hits on my plane, although none did any serious damage. The LILY continued its roll and spun-in in flames. I recovered on the left side of the remaining bombers, and I now saw only six left. I made two more runs on the rear LILLY’s but observed no real damage from my fire. Three more of the bombers were shot down by other fighters, two were in flames, before they arrived over the transports in the Gulf. As the remaining three bombers dove thru the thin layers of clouds over the ships, the ships’ AA opened fire. I pulled out to the left and headed back to point NAN. I observed two planes crash into the water that had probably been hit by our AA fire, and one was close alongside a large landing ship just off shore. At Point NAN I joined up with Lt. Seitz, who had turned back, and Lt. (jg) Hunting. Aswe were all quite low on fuel we headed for our base. I landed aboard with from 8-10 gallons at 0930.

Joseph crossed the bar in July 2015

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

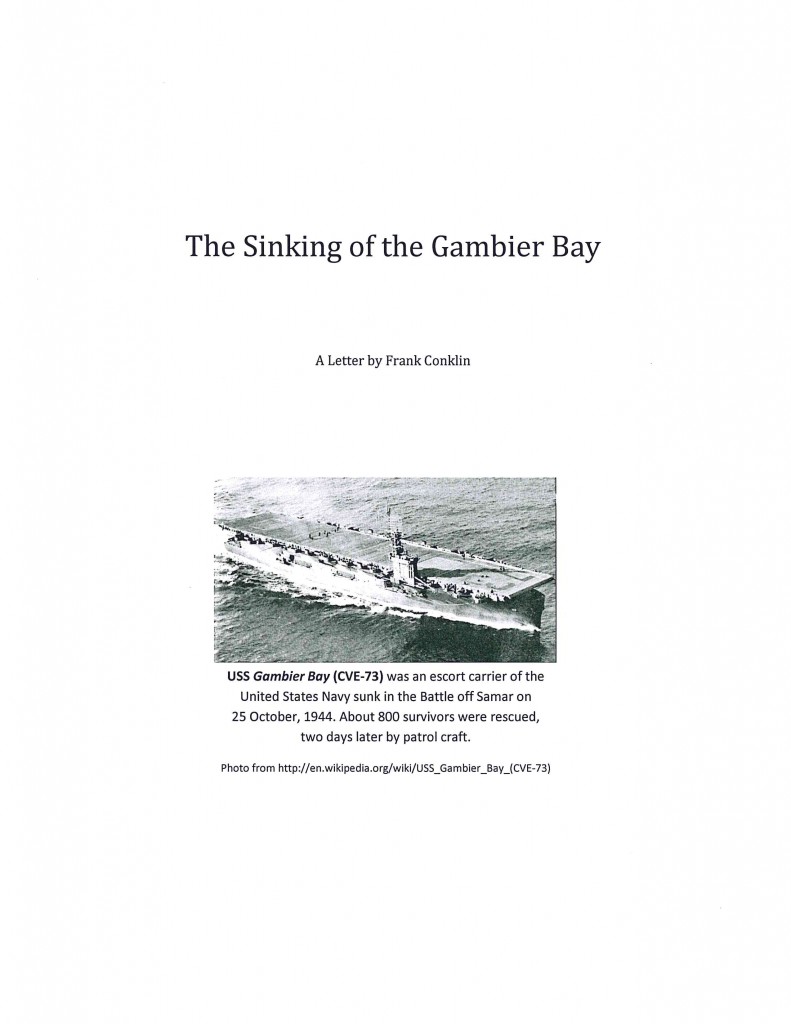

USS Gambier Bay Sinking – 1944

By: Joseph E. McQuade

I first boarder the USS Gambier Bay 73 in September 1943 leaving my wife Joan behind to destination in the Pacific Ocean, only God had knowledge.

At 23 it felt like a life time away till I would see land once more. They kept us busy preparing for anything to come our way.

The morning of October 25,1944 we were awaken to the barrage of 8″ shells from the Japanese heavy cruisers.

First it was the forward engine to be taken out slowing the Gambier Bay although the battle was only hours it felt like days. The rear engine was taken out.

Somewhere around 9:00 am the ship started listing dead in the water when the order came down to vacate before the ship had sunk.

Jumping starboard my friend Fred Yeoman and I hit the water. With no raft we Swam and swam, searching anything to climb aboard. Soon enough a giant wave reached me high enough to locate a floating raft loaded with wounded on the wooden floor. So I grabbed on to a rope and held fast, 3 nights and 4 days of no food or water till finally rescued climbing the mesh latter side the ship. Last thing I remember is the Captain saying hot meal or bunk. To this day I don’t remember what my answer was!

I returned home for a week with my wife Joan for Christmas. Then stationed in San Francisco till my discharge, November 1945. I’ll never forget that day I lost several fellow sailors and pilots friends.

Today I am 91 and going strong with wife Joan, daughters Jo Ann, Mary, sons Ron, Richard, Joe, Jr. Past But Not Forgotten: William and Michael, 11 grandchildren, 15 great grandchildren, and “1” great-great granddaughter “Aubrey”.

When my son-in-law said I have a story that needs to be told, as Col. Oliver North would say. So my story written by Harold Herrington, the one, the only “Dinkiedow!”

And I approved, AM3 Joseph E. McQuade, Sr.

* * * * *

(Click on link below for video – Taffy III – Dragons off Samar)

Joseph crossed the bar in December 2013

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Aptos Veteran, Richard Person, Recalls the

“Last Battle of the Big-Gun Warships”

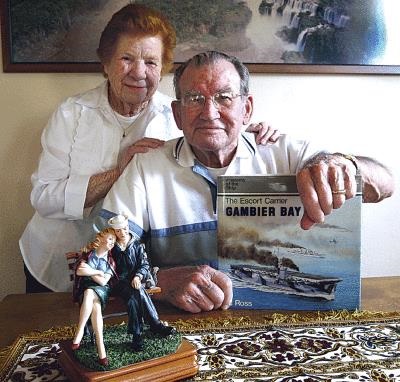

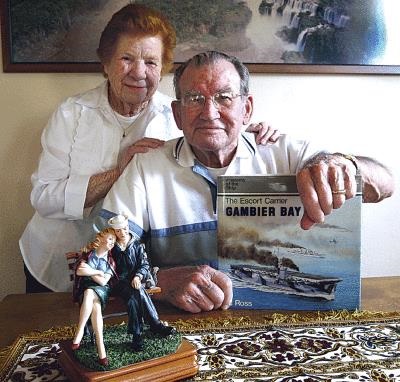

Richard Person of Aptos, pictured with his wife Ruth, survived the sinking of the USS Gambier Bay during one of the most savage naval battles of World War II.

Richard Person of Aptos, pictured with his wife Ruth, survived the sinking of the USS Gambier Bay during one of the most savage naval battles of World War II.

*

In a 35-man raft, Richard Person and 85 other Navy men, clung to each other, belly-to-belly, most of them holding onto the outside of the tube.

The men with the worst injuries were put in the center to keep their blood from working the sharks into a frenzy. But the sharks, fins thrashing, still attacked, pulling some of the men away.

One of the survivors, Richard Person, 85 and originally from Illinois, has been living in Aptos with his wife, Ruth, for the past 65 years. He is charming in a grandfatherly way and his eyes are warm behind black rimmed glasses when he smiles.

He survived one the most savage naval battles of World War II: The Battle of Leyte Gulf in the South Pacific in 1944. It has come to be known as the last great battle between big-gun warships.

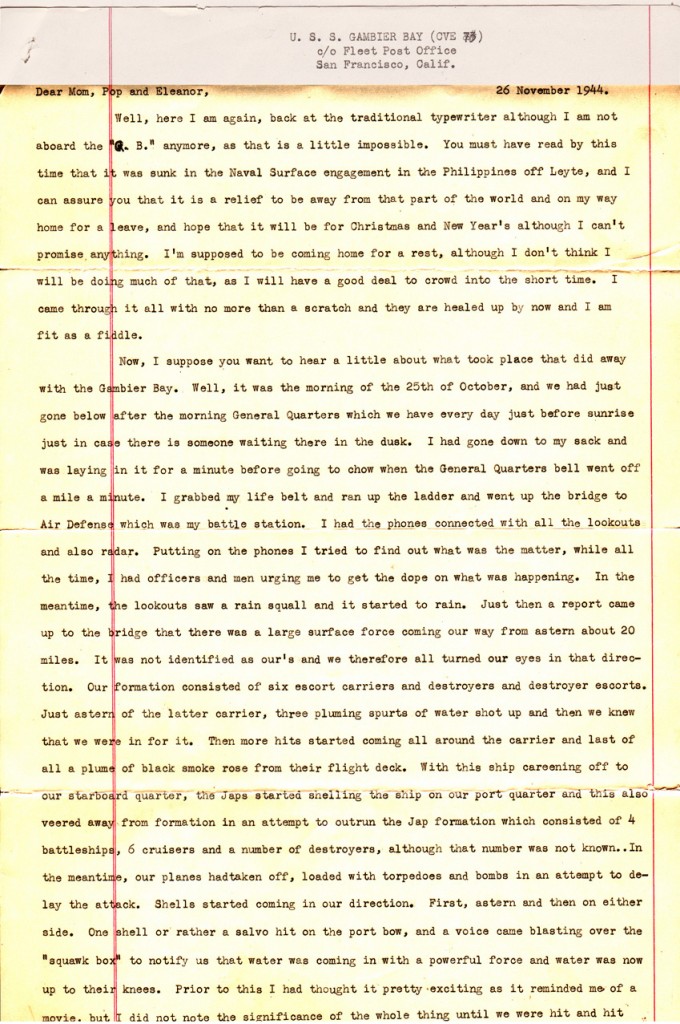

Person served as a throttleman in the engine room of the USS Gambier Bay, a 512-foot steam-powered escort carrier, that sailed off the coast of Samar, an island in the Philippines, with 12 other U.S. ships in a support unit called Taffy 3. Their mission was to support the U.S. landing to re-take the Philippine Islands. On Oct. 25, just after sunrise, 23 Japanese ships ambushed “Taffy 3” by sailing under cover of fog into their midst and opening fire.

Person, a 19-year-old machinist second class, was at the throttle in the aft engine room.

“I remember a shell coming down through the deck into the engine room and hitting the boiler,” he said. “It exploded right there, but I remember being taken aback first by the light from outside, piercing down into the engine room through the hole the shell had made.”

Within 10 minutes of first sighting the Japanese, shells were exploding all around their ship, according to Petty Officer Second Class Tony Potochniak, who was also aboard the Gambier Bay, founded the USS Gambier Bay Association in 1968 and has researched the battle extensively.

“We were out-gunned by the bigger ships and our 20 and 40 mm anti-aircraft guns might as well have been pop guns at that range,” he said.

The U.S. destroyers in the group, the USS Johnston, USS Hoel and the destroyer escort USS Samuel B. Roberts, charged the oncoming Japanese fleet, knowing it was a suicide run, in order to divert them so the Gambier could get its planes in the air, Potochniak said. Many of the planes didn’t have bombs or torpedoes but made “dummy runs” to fake-out the enemy.

As shells churned the water and tore the ship apart, the Gambier’s chaplain, Rev. Vern Carlsen, reported what was happening on deck and what part of the ship the shells were going to hit over the loud speakers, Person said.

Back in the aft engine room, Person was surrounded by wreckage and up to his knees in sea water. The ship had three main compartments and two of them were flooded.

The Gambier was taking point-blank shell fire from enemy cruisers, the Tone and the Chikuma, even as she sank, Potochniak said, which he added was “not very kosher” of them.

Potochniak rushed onto the slanting deck and could see the gun flashes of the Tone firing on them before sliding down a rope into the ocean.

The Gambier was dead in the water, Potochniak said. Other ships in Taffy 3 were able to continue fighting ducking under the cover of a passing squall.

U.S. destroyers weaved in and out of the smoke and fog, laying smoke screens, attacking and maneuvering, but two were sunk, he said. More than 100 aircraft from the units Taffy 1 and Taffy 2 flew in to assist.

The Gambier sounded its alarm to abandon ship as it listed on its side, water rushing in and fires burning, Person said.

“We shut the engine down as best we could, because we had live steam, and then ran topside,” he said.

He burst through fire curtains onto the deck as a shell struck a fully fueled aircraft still on the flight deck, Person said. The explosion blew him back 10 feet and slammed him against the bulkhead. Though he didn’t feel pain at the time, he had severely injured his back.

The ship was listing so far that, after he recovered from the explosion, Person stepped right over the railing and landed in the water. As the ship rolled, he swam as fast as he could to get away from the flight deck, which hung far out over the hull, and dragged several men under as it hit the surface. Life rafts were launched and men were hauling each other aboard.

The position of the USS Gambier Bay was not correctly reported when it went down, and over a two-day period 1,110 men from all the ships that were sunk in Taffy 3 drifted in overcrowded rafts between 35 and 45 miles in shark infested waters, Potochniak said. They had no fresh water and few rations.

Person remembers the ocean swell carrying him up to where he could see the Japanese ships firing guns at their rafts. They could see shells coming right at them. As they dropped into the troughs of the waves, the shells whooshed directly over their heads. The men aboard a nearby raft were hit.

Early in the morning after the Gambier Bay sunk, in dim light, Person vaguely recalls a Japanese ship passing nearby. Japanese sailors lined the deck, but instead of firing their guns, they stood at attention and saluted.

Potochniak confirms the story in which the Japanese sailors aboard the Yugumo-class destroyer Fujinami commanded by Tatsuji Matsuzaki passed the Americans in life rafts and made a gesture of respect.

Tatsuji was killed in the following days when his ship was sunk by American forces, Potochniak said. The Japanese commander was posthumously promoted to captain.

Potochniak explained that the story of the unusual event has only recently been brought to the attention of wider audiences.

Two days after the sinking, a U.S. patrol craft found the raft he was on, Person said. To make sure they were Americans in the raft, the crew yelled down at the survivors, “Who won the World Series?” The survivors answered and were hauled aboard.

Five ships from Taffy 3 were destroyed during the battle and there were 960 casualties, Potochniak said. Of the 860 aboard the USS Gambier Bay, 137 died.

Person was sent to Santa Cruz in 1945 and stationed at the Casa Del Rey Hotel, near the Beach Boardwalk. He met his wife, bought a small house in Aptos and started a family that now includes grandchildren. Though his war experiences were more than 65 years ago, he still has panic attacks, nightmares and wakes up in cold sweats, Person said. A long time has passed since he served on the USS Gambier Bay, but some things can’t be forgotten.

Published by Joel Hersch in Santa Cruz Sentinel – November 11, 2010

Photo by Dan Coyro

Richard crossed the bar in October 2014

Ruth passed in April 2021

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Alexander “Chick” Zuckerman

*

When and where were you born?

I was born in Passaic, New Jersey on April 29, 1923. When Wall Street crashed in 1929, we didn’t feel it in our house because we were so poor. By the age of 12, I joined a drum and bugle corps, the only Jewish corps in the world. I learned a lot about anti-Semitism. As we marched down the street you could hear the comments. Life changed for everybody on December 7, 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. In January 1943, I left for the Navy. After boot camp, I was assigned to an aircraft carrier named the Gambier Bay, which was assigned to General Douglas MacArthur for his return to the Philippines. On October 25, 1944, our ship was sunk. I was in the water for 4 days. Thirteen-hundred men went into the water, and 400 came out. When I returned to civilian life, I married, purchased a bakery shop, which I eventually sold, and then became a salesman for Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing (3M) and other companies. I was very involved in the Clifton Jewish Center in Clifton, New Jersey, helping them to raise money by starting an annual community carnival.

What is your current state of mind?

Excellent, and the reason I say that is because I’ve been taking a pill for my memory for over 45 years. It’s made up of vitamins and minerals. I like to think my biggest asset besides the clarity of mind is my humor.

What is your favorite way of spending time?

Sitting and talking with people. Sometimes I tell a joke to get it started.

Which living person do you most admire?

There are three people: my son, Stephen, and daughter Helene, and my friend, Ben Wiesel. Stephen went to the University of Boston and graduated with a degree in journalism. He was associate editor of the San Francisco Chronicle for 18 years. Helene put herself through school and has practiced Hellerwork for 28 years. Ben has integrity and clarity of mind. What I like about him is that he is a loyal friend and generous to a fault.

What is your most treasured possession?

Once again, my children because without them there would be a total void. And my good health.

When and where were you happiest?

When you go into the water, after two days you kind of give up on someone coming to get you. When you finally see a ship on day four – that’s when I was the happiest.

What is the trait you most admire in yourself?

Being upbeat, friendly, generous, and a positive thinker.

What is the trait you most admire in others?

Loyalty, friendliness, sincerity, and enthusiasm.

If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be?

I would get out of this wheelchair. I would give anything to be able to get up and dance the meringue or salsa.

What do you consider your greatest achievement?

There are a few: being in the drum and bugle corps; being with MacArthur in the Philippines and staying alive for 4 days in the water; helping the Clifton Jewish Center get on their feet.

What is one thing about you that people would be surprised to know?

I cry easily. And at one time I was a professional clown.

What is your motto? (words you live by or that mean a lot to you)?

There are two: “The older the fiddle, the better the tune”; and “Don’t count the years, make the years count.”

What one piece of advice would you give about healthy aging?

Have a healthy diet; stay away from dessert; eat fruit. Exercise; going to the gym can do more good for you than all the pills you can swallow. Tell a joke a day; if everything else fails, tell it again.

Published in the Los Angeles Jewish Home newsletter – 2013

Al crossed the bar in January 2017

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Eulogy for Robert (Bob) Boggs

By: Barbara Boggs Schlaff

October 26, 2013

Good Morning

Survivors from the Gambier Bay, Madam President, Board of Governors, members of the Gambier Bay VC-10 Association, family and guests.

My Father, Robert Boggs, would have celebrated his 90th birthday this year on September 27th. Attending this reunion was to be his present. He took his final flight on July 1st, but I am sure his spirit is with all of us today.

His pride and love of his Navy career and the many years as President of this association was only surpassed by his love for his family. Dad had four children, myself, Susan, Beth and Scott, 4 grandchildren and 4 great-grandchildren. We all spent the week before his passing at Hilton Head Island. Dad really enjoyed our annual family vacation at the beach.

Dad’s work and Navy Reserves took him away much of our childhood, but in retirement he never missed a family vacation, holiday or special occasion. After Mom passed away, 8½ years ago, Dad moved to Florida full time. He and my brother, Scott spent every weekend renovating the condo that my parents owned. Dad soon moved in with Scott and devoted his weekdays to chauffeuring his youngest granddaughter, Ashley, Scott’s daughter, to and from school, swim practice and horseback riding. They both shared a sweet tooth, which was often satisfied by a stop at the French pastry shop on the way home from school.

We also have a condo in Florida which enabled me to visit Dad frequently throughout the years. He also came to Michigan for the summers to spend time with me and his great-grandchildren. He delighted in taking them to the Blue Angels Air show and explaining the aircraft. I have a cute picture of Dad standing in front of a Blackhawk helicopter with the girls just as a loud flyover occurred. Dad was smiling and the girls were covering their ears from the noise. Dad knew not to wear his hearing aids to an airshow.

Dad wore his Navy aviator T-shirts and his Gambier Bay VC10 ball cap every day. Where ever we went, he attracted a crowd of grateful civilians who thanked him for his service to our country. Shopping required twice the time as Dad would talk to each one of them. It’s wonderful to see the gratitude and respect that people have for “The Greatest Generation”.

A few years ago, Dad, Scott an Ashley were flying to Columbus, Ohio for Christmas. As they were waiting in Starbucks two Delta pilots walked up and immediately started talking to Dad. They were also Navy pilots and they had a great conversation with Dad talking about the various planes they had flown. They were piloting an earlier flight to Atlanta, and asked if Dad was on their flight. He was not. They took the tickets and returned. They said it would be an honor if Dad flew with them. Well, it didn’t stop there. They brought Dad, Scott and Ashley on board early, sat Dad and Ashley in the Pilot and Co-pilot seats and instructed Ashley how to set the tower and departure frequencies on the radio. They seated them in First class and during the flight, made an announcement to the passengers of Dad’s rank and 28 years of service.

As the self- proclaimed Navy Brat of the family, Dad and I put together an 85 page album of his military career. While sorting through all the pictures that he kept, I would ask Dad, if he was scared on some of his missions. He said, “Barbara, it was my job and a great honor to serve my country.”

His humble reply only increased my admiration of the “Greatest Generation”. One of the most interesting photos was one of Dad and his torpedo bomber crew. It was signed by his crew members, the gunner, Dan Merriam, who said “Good luck from the eyes in the back of your head, and the radio and radar operator Ken Woods, “Here’s to the fellow I hope always brings me home”. That is the way we all felt about Dad, a wonderful soul, a humble man and a mentor for his family.

Dad was always the first to be ready to go anywhere, Mass, swim meets, football games, and trips. He would be patiently waiting in the car while we children ran around finishing the last minute details. He also contributed a lot of humorous material for us in his later years. I always left chocolate in the refrigerator at my condo in Florida as his treat for checking that everything was okay in the summer months. I must have run out, so Dad had Scott take a picture of him lying on the floor with the refrigerator door open, pointing to the empty shelf where his chocolate should have been.

For the last 8 years, Dad took an annual ski trip to Salt Lake City, Utah with my brother Scott and his daughter, Ashley (and no Dad didn’t ski, but loved the hot tub surrounded by snow and sleigh rides to dinner on top of the on the mountain). The next Christmas with the help of my brother, they superimposed Dad’s face onto a downhill skier which he sent to all of us who wondered what he actually did do in Salt Lake City.

We girls rotate the family Christmas. One year, Dad came to Columbus, Ohio to celebrate at Susan’s. He had a bad cold. I had brought homemade Greek Baklava (his favorite) and he asked me to put some away until he felt better. Caught up in all the family festivities and the children, I must have forgot. But the following morning, under his bed was a Ziploc container of baklava that he had stashed sometime during the night.

Dad was everyone’s friend from the people he met at the malls, the Mom’s on Ashley’s swim team and our neighbor, Alan Mulally, Chief Executive Officer of Ford Motor Company. His stories, even if somewhat embellished, captivated all audiences.

Active until the end, Dad was on his way to church when he had a fatal aneurism. Put on life support, we all made arrangements to fly to West Palm Beach on the next flight to say our goodbyes. With only sketchy details of the situation, my Delta representative assured me Dad would be just fine as he had so many flights booked to Detroit, Tucson and Columbus in the coming months. Unfortunately, God must have needed a trusted pilot for some mission. He will be greatly missed by all of us.

I would like to end this memorial with my favorite prayer. Ever-watchful God, you are our refuge and strength in every time and place. Send your blessings upon those who are serving our country in the armed forces. By your powerful spirit, shield them from all harm. Uphold them in good times and in bad, especially when danger threatens. Let your peace be the sentry that stands over their lives, so that they may return safely. Put an end to wars all over the earth, and hasten the day when the human family will rejoice in lasting peace. Grant this through Christ our Lord, our Son, who lives and reigns as the Prince of Peace, both now and forever. Amen

Front – Scott Boggs, Robert (Bob) Boggs, Barbara (Boggs) Schlaff

Back – Beth (Boggs) Ashe, Susan (Boggs) O’Rourke

Bob crossed the bar in July 2013

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Up From The Peril Of The South Pacific In WWII

He Floated 5 Days In The Ocean And Lived To Tell It

It was 50 years ago, and 18-year-old Fred DiSipio was floating somewhere in the South Pacific on a pile of wreckage.

He was badly wounded. He hadn’t eaten in five days. His only water came from some passing rain showers.

Eleven other sailors who had clung to the same wreckage had all died during the five-day ordeal. Two were killed in a shark attack.

“It was at this point I started thinking I should be getting ready for my prom at Southern (South Philadelphia High School). And I began thinking this is all a dream,” said the Cherry Hill resident.

DiSipio’s ship, the aircraft carrier Gambier Bay, was sunk in one of the major sea battles of World War II.

The South Philly kid, near death, was found by chance by a passing PT boat 200 miles from where his ship had gone down. He would survive to become a major record-industry promoter and wealthy racehorse owner.

He calls his survival a “one-in-a-million” fluke. Although he won a Purple Heart and Presidential Unit citation for participating in the sea battle, there is no independent proof of his remarkable five-day odyssey. “It never made the newspapers because those kind of stories were very common. I didn’t do anything unusual,” he said.

Later this month, DiSipio and thousands of other survivors of the Battle of the Leyte Gulf will gather at anniversary reunions to share memories of the big fight off the Philippines that began October 23, 1944.

The Japanese threw all their big ships against America’s effort to retake the Philippines.

An enemy decoy plan drew most big U.S. fighting ships away from Leyte, where hundreds of transport and supply ships were landing an invasion force.

It was a force of six lightly armed, thin-skinned smaller aircraft carriers and seven destroyers that faced a Japanese fleet of 25 – four battleships, eight cruisers and 13 destroyers.

DiSipio had dropped out of high school to join the Navy at age 17. “The war was at a fever pitch and everyone wanted to get into it before it was over,” he said.

In the mismatched battle October 25, DiSipio’s Gambier Bay was soon to become the first and only American carrier sunk by surface-ship fire. Others were destroyed by submarine or air attack.

“All hell broke loose,” he recalled. “We were hit by salvo after salvo. Once they got the range they didn’t miss. One battleship (the Yamato) fired 18-inch guns.” DiSipio said he saw those huge shells go through one side of his ship and exit the other without exploding.

At one point, he saw a friend decapitated, and he was soon wounded. He said he was on the listing flight deck clinging to a cable, afraid if he let go he would slip into a huge fire.

He was saved by a tremendous explosion that blew part of the ship into the sea, DiSipio said. He had wounds in the shoulder, head, back and left leg, and fractured ribs.

He joined other men in the ocean in lashing together bits of debris into a sort of raft. “I had a ringside seat of the battle. I saw the first kamikaze attack of the war. I watched a Japanese ship smash right into the forward elevator of the (carrier) St. Lo.”

He watched his own ship sink. An enemy destroyer sailed close by, and he saw a Japanese cameraman taking film of the American survivors.

Sharks attacked the first day. “I was the most badly wounded, so I was put in the center of the raft,” DiSipio said. “Everybody was partially in the water. The shark attack lasted about half an hour. We poked at them with pieces of lumber or kicked at them. Two men were killed. . . .

“I was burned to a crisp by the sun. At night I froze. Eighty percent of my body was always in the water. We had caught a strange current that took us far away from all the other survivors.” One-by-one the other men died of injuries, exposure or were swept off the raft.

After his rescue, DiSipio spent 13 months in military hospitals. It was three months before his family discovered he was alive.

After the war, he “drifted” into the entertainment industry. “I got into promotions and marketing,” he said. “I worked with everyone from Chubby Checker to the Beatles to the Motown people up to Bruce Springsteen and Michael Jackson.

“I retired about four years ago, and I spent a lot of time in Italy every year,” he said.

The Battle of Leyte Bay has been called the largest naval battle in history. DiSipio witnessed only one part of it when four American ships were sunk and nearly 800 sailors killed, including 122 on the Gambier Bay.

But American planes crippled three Japanese cruisers. The Japanese commander was hampered by poor communications and did not know how well his ships had done. He broke off the attack and withdrew.

*

By Ron Avery, Daily News Staff Writer – Posted: October 3, 1994 – philly.com

Fred crossed the bar in November 2013

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

May 2014 – Dean Moel received his membership certificate for 50 consecutive years at the American Legion Stinocher Post 460 in Solon, Iowa. Actually, Dean has been a member for 68 years!

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Owen Wheeler – Lucky Streak Kept Local Flyer In The Air

Owen Wheeler grew up in Ceredo and went on to a distinguished military career which lasted more than 20 years, a career that could have ended when his aircraft crashed at sea, or when Japanese forces sunk his ship in the South Pacific, but luck stayed on Wheeler’s side.

He has memories of burning real candles on the family Christmas tree back in Ceredo, of working in his uncle’s garden for $1 a day and of riding a horse three miles to school.

“My father worked at Columbia Gas,” Wheeler said. “Every year the plant had one special day for employees and their families to attend Camden Park. The roller coaster may still look the same, but the real steam-powered train is gone now. They once had a lake with rowboats and a nice swimming pool — they’re gone as well. Things just don’t stay the same for long.”

Wheeler tried high school football, but Friday nights eventually found him watching football games from the bleachers.

It was Wheeler’s grandmother that started his financial career when she gave him a pig that was the runt of the litter.

“From that runt of a pig, I eventually ended up with 20 or so pigs that I would sell for $5 each,” he said. “Paying for a veterinarian would sometimes cut my profits, but I managed to still make a little money.

During the growing season, Wheeler sold produce at the old farmer’s market located along 6th Street in Huntington.

“We would sell vegetables from the back of my father’s Model A Ford truck,” Wheeler said. “Then I would always go to this restaurant across from the Huntington courthouse on 4th Avenue and buy a fish sandwich for a quarter. That was expensive back then, but they were good.”

Wheeler tried a few semesters at Marshall, and then decided to study agriculture at West Virginia University in Morgantown, with about the same results. Finally his father helped him find a federal job at an accounting office in Washington, D.C.

“While in Washington, I attended night classes at George Washington University,” Wheeler said. “When a fellow classmate took me on a ride in a Piper Cub airplane, I was hooked on flying.”

For the next few months, Wheeler took flying lessons at the Congressional Airport in Rockville, Maryland, under the civilian pilot training program which was paid for by the government with an obligation to serve in the military — and the Navy soon called.

Long before Wheeler would ever be awarded his wings and become an ensign in the United States Navy, he went through a lot of training.

The long upward climb to be awarded his wings started at Anacostia Naval Air Station in D.C. This phase began at the grassroots level with basic characteristics of flight, wing lift, flight controls, radio communications, instrumentation, and general preflight inspections.

Next came the Boeing Model 75 Bi-wing Stearman which involved multiple stages of flight at Rodd Field in Corpus Christi, Texas. It was at this stage that Wheeler learned about the consequences of bad judgment in the cockpit when a fellow student was killed.

Wheeler’s training continued on various types of trainer aircraft. Classes continued to become more advanced with different aircraft. Training had now advanced to formation flying, navigation in adverse weather, dropping bombs and guiding torpedoes to a target.

Just before being shipped off to Opa-Locka, Florida, for additional flight training, Wheeler was promoted to the rank of ensign and awarded his wings March 15, 1943.

No sooner was Wheeler finding out where all the area “watering holes” were located, than he was transferred again. This time it was to Astoria, Oregon, for advanced bombing techniques, dropping low level torpedoes and night flying.

By the time Wheeler began practicing aircraft carrier landings at Holtville, California, rumors began circulating about war. He believed the rumors had merit when they left for Pearl Harbor on the ill-fated aircraft carrier USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73). Even Wheeler’s first training flight off the decks of the USS Gambier Bay was one to remember.

“We were flying formation for less than an hour when my wingman said I had an oil leak,” Wheeler said. “I was instructed to return back to the carrier when the engine seized up. I floated in the water for nearly six hours before being rescued.”

After one mission, Wheeler complained about the lack of power in his plane. On the very next flight another aviator flew that same plane, which lost all power on take-off and killed the pilot. On another occasion, he was supposed to fly a mission and another aviator took his place. The plane was shot down, and the pilot spent over a year in the hospital recovering.

Historical events of the USS Gambier Bay are well documented. In the short 15 months of sea duty, the carrier was involved in more than its share of battles in the open sea. An Oct. 25, 1944, attack sank the vessel.

“An 8-inch shell from the Japanese Heavy Cruiser Chikuma left us dead in the sea and taking on water,” Wheeler said. “It was the additional heavy shelling of the Japanese Battleship Yamato at close range that left us all in shark-infested waters for nearly two days waiting for rescue. The majority of the 800 survivors were rescued. Until we were picked up, all we could do was wait and watch the USS Gambier Bay slip beneath the waters of the South Pacific.”

Wheeler’s flying career with the United States Navy continued on until July 1963 when he retired as a Lt. Commander. His career took him throughout Europe to such places as England, Germany, Turkey, North Africa, Greece, Spain, South America and Alaska.

The United States Navy spent a lot of our tax dollars training Wheeler to fly. Wheeler feels that America got its money’s worth.

*

Story by: Clyde Beal, Herald Dispatch in Huntington, West Virginia

(September 21, 2014)

Owen attended the Taffy III reunion in San Diego.

He crossed the bar on October 28, 2014.

* * *

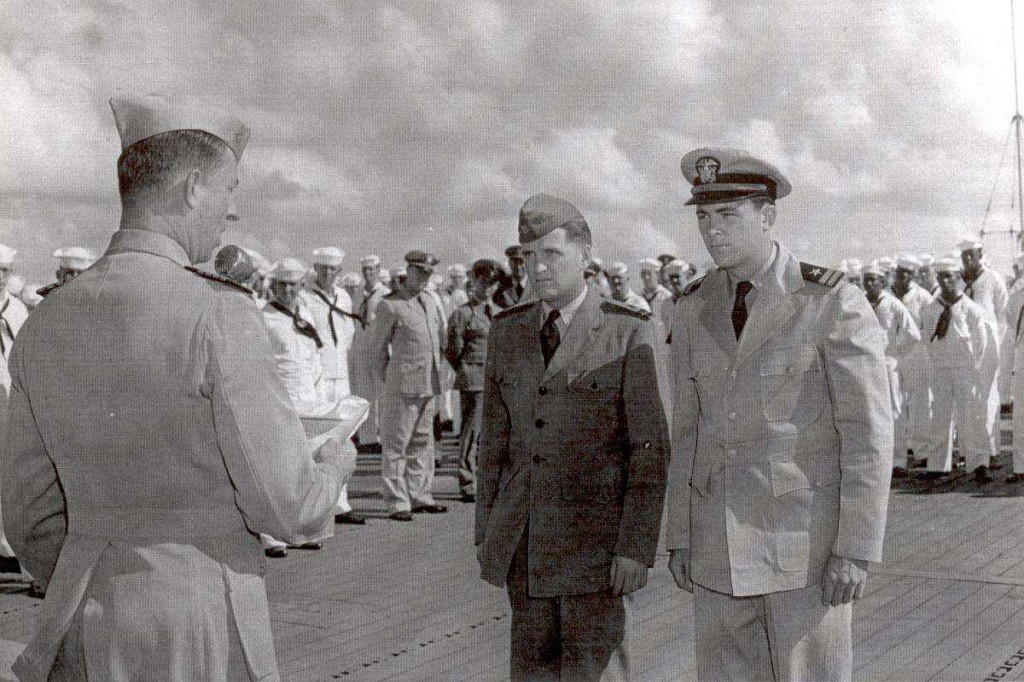

Owen E. (“Wheels”) Wheeler (LCDR, USN [Ret.]) was born November 12, 1920, in Huntington, WV. He served his country as a U.S. Navy pilot, enlisting soon after the start of World War II. Almost exactly 70 years ago, the ship on which he was serving, the escort carrier USS Gambier Bay, was hit by enemy fire during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. He jumped from the sinking ship into the Pacific Ocean, where he remained adrift with hundreds of other shipmates for almost two days. After his rescue, he joined a re-formed squadron and served the remainder of the war aboard the USS Fanshaw Bay. In 1945, Owen flew the official surrender papers of the Japanese Imperial Navy, North Pacific Fleet, from Mutsu Bay to Yokohama, Japan. In September 1947, he was aboard the USS Missouri, bringing President Truman home from the Inter-American Conference in Rio de Janeiro. Owen remained in the military, serving as a pilot in the U.S. Navy, until 1963, when he retired and settled in South Carolina, the birthplace of his wife, Bonnie Beamguard Wheeler. The Wheelers, who married in 1949, continued to call South Carolina “home” for the rest of their lives. They travelled extensively and appreciated the people, geography, and cuisines of every place they visited. Owen never wanted to visit the same place twice. His life-list of places visited includes more than 120 past and current countries of the globe. After his retirement from Champion International Paper (formerly U.S. Plywood), Owen volunteered at the Soup Cellar, preparing meals for the homeless, and at Meals on Wheels, delivering meals to homebound clients until he was in his 90s and thereafter working to pack meals for delivery. He also volunteered for the Red Cross, working in the pharmacy at Moncrief Army Community Hospital on Fort Jackson. He continued to volunteer faithfully until his death. In addition to his regular volunteer work, Owen was active in his church, Incarnation Lutheran Church. At home, he loved to cook and to experiment in the kitchen. He was most proud of his service to his country, which manifested in many ways, from his career in the U.S. Navy to his commitment to his jobs, employers, and employees in civilian life, to his love of and devotion to his family, and his voluntary service to church and charity. Owen died shortly after returning from a military reunion in San Diego, commemorating the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. There, he met many old friends and shared his personal stories with midshipmen from the U.S. Naval Academy. Owen died at home on October 28. He is survived by his daughter, Jennifer A. Wheeler, of Vernon, CT, by Barry Chernoff, of Middletown, CT, and by his sister, Donna Jean Ball of Kenova, WV. He was predeceased by his beloved wife.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Lt. (jg) Dean W. Gilliatt

Another operational accident that day was far more tragic to the men of the Gambier Bay. The carrier that day was responsible for two combat air patrol groups. Each patrol was carried out by four airplanes, who searched predetermined patterns above the carrier force, ready to be vectored, or dispatched to any point on the orders of the Combat Information Center. Lt. (jg) Dean Gilliatt was flying one of the planes of the second patrol. From the bullhorn on the bridge came the order, “Pilots man your planes,” and the four fighter pilots scrambled from the ready room to the flight deck and got into the cockpits. “Stand clear of propellers,” came the next order, and then “Start Engines.” The pilots engaged the starter mechanisms, the engines whined, coughed and started, and they were read to launch.

Since fighters were expected to be in the air for an extra-long time, they were hung with wing tanks. Normally, the wing tank was attached to the starboard wing of the Wildcat, and the pilot adjusted the controls before takeoff to compensate for the additional weight to the starboard side. But this day, the plane captain of Gilliatt’s fighter was unable to fix the tank to the starboard wing, so he moved it over to port. he forgot, and so did Lieutenant Gilliatt, that the plane was trimmed for extra weight to starboard, when actually the weight was on the other side.

Lieutenant Gilliatt began a free-run takeoff. The moment the plane began to move he knew he was in trouble, but the short and narrow deck of the Kaiser carrier give him no margin. As the wheels left the deck the port wing was dropping, and the plane nosed over to the left of centerline in spite of the pilot’s obvious frantic efforts to maintain the proper attitude for takeoff. For a moment it seemed that he might make it — the Wildcat needed only a foot more altitude to clear. But the landing gear caught in the top of the port side 40-mm gun mount just forward of the island, and sent the plane over the side, into the sea at a forty-five-degree angle. The plane went down, but came up and floated horizontally, as if flying on the surface of the sea.

The crash alarm sounded the moment it became apparent that Gilliatt was going to hit the gun. Commander Huxtable was in the ready room, and he rushed to the catwalk, and came outside just as the ship passed by the floating plane. He could see Gilliatt in the cockpit, his head slumped forward on his chest, unmoving. Either he had broken his neck on impact or he had been knocked out. The ship moved inexorably past the wreck, and men on the flight deck prayed that the pilot would come to and unsnap the safety belts. But they went past, and the plane sank, and when the escort came up, the sea was empty.

Lieutenant Harders, Gilliatt’s best friend aboard the Gambier Bay, stood on the catwalk outside the Aerology office, watching with Lieutenant Odum. Tears began streaming down Harder’s cheeks. “Oh, why couldn’t it have been me instead of Gil? He had so much to live for,” sobbed the flyer. Gilliatt had married in these frantic war years, and he had learned just before they left for war that his wife was about to have a baby. So much said, there was no more to say. The call came from the bullhorn for another pilot; the combat air patrol required four planes and only three were in the air. In a moment another fighter pilot was manning his plane, and in a minute he was off the deck, taking the place of Lieutenant Gilliatt. The demands of the war left no place for personal sorrow.

Dean Gilliatt was KIA – June 19, 1944

*

Excerpt from The Men of the Gambier Bay: by Edwin Palmer Hoyt

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

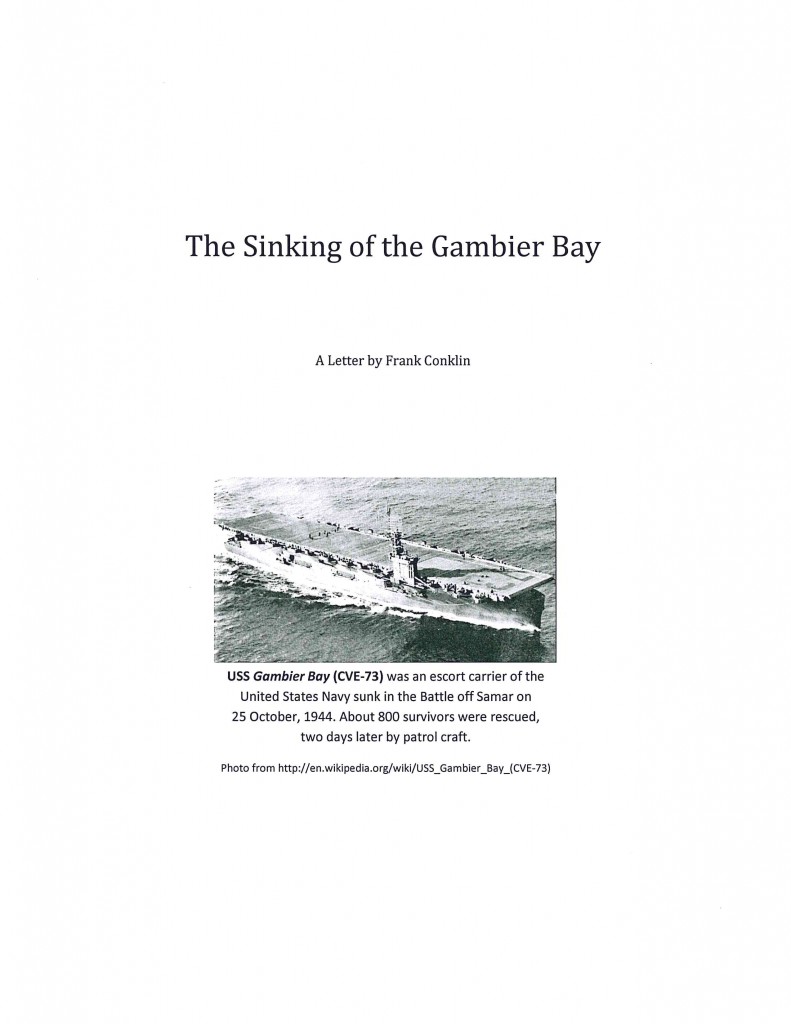

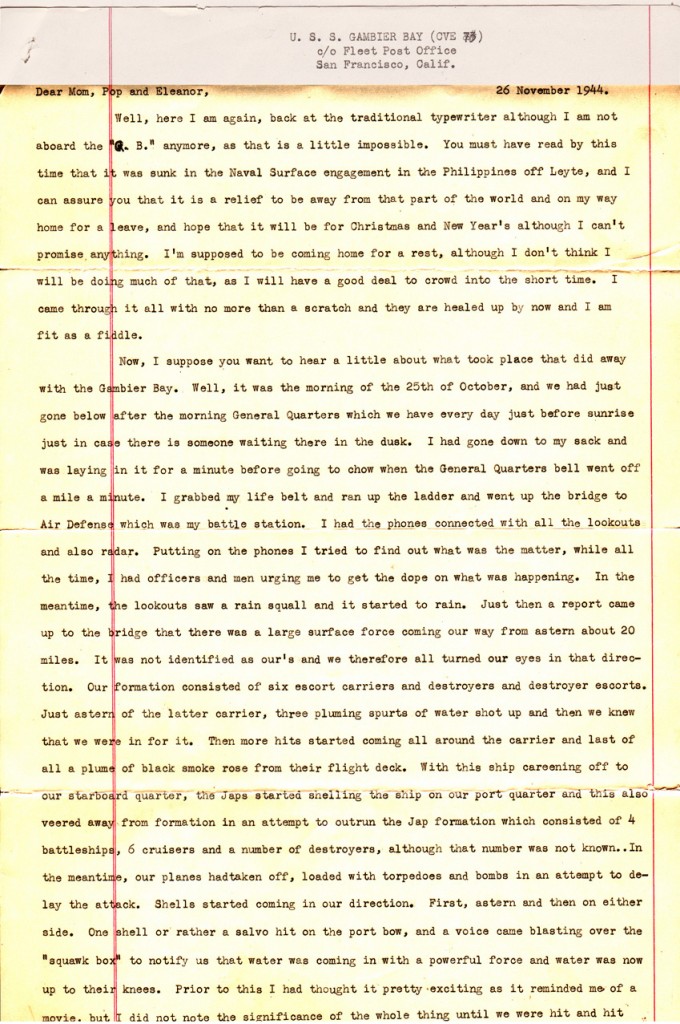

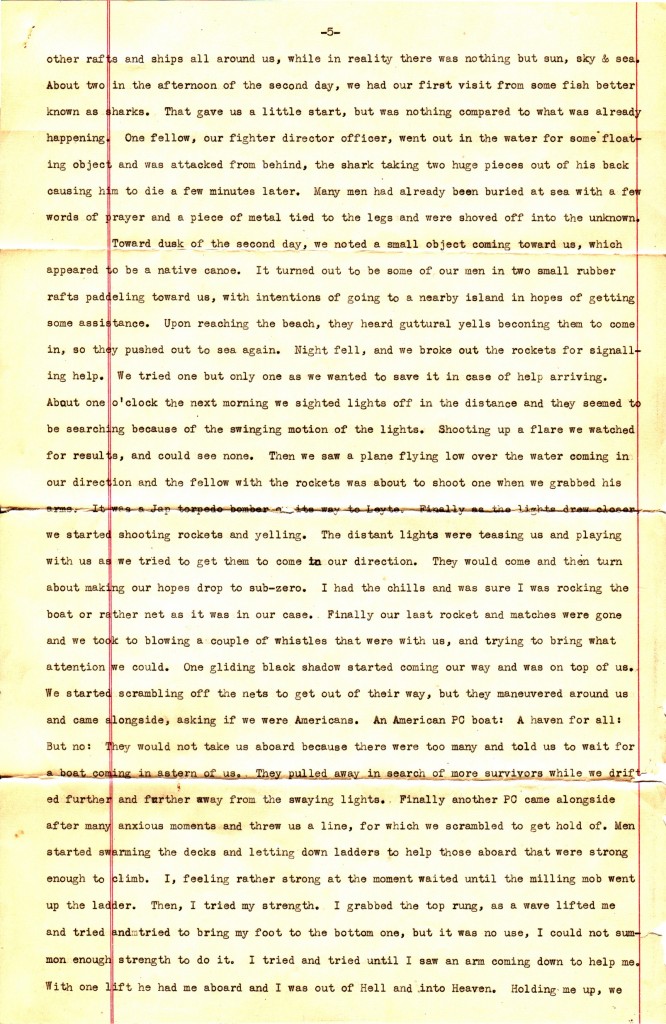

The Sinking of the Gambier Bay

A Letter By Frank Conklin

Frank crossed the bar in January 1976

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

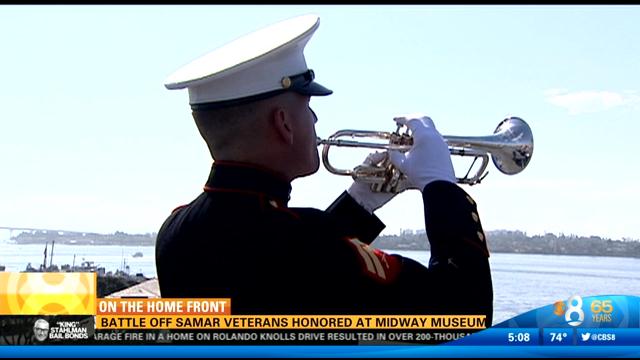

WWII Reunion Brings Tears, Memories – Dwindling Group of Battle Off Samar Survivors Honor Those Who Died In Famously Mismatched

Sea Conflict With Japanese

DOWNTOWN SAN DIEGO — On Saturday morning, almost 70 years to the hour after the Battle off Samar, Cletus Ring needed only a little urging to share his memories of the brief, bloody World War II conflict known as one of the greatest mismatches in Naval history.

In the Philippine Sea off east Samar on October 25, 1944, a Seventh Fleet task force of 13 lightly armed U.S. support ships known as Taffy 3 took on 23 of the biggest and most heavily armed ships in Japan’s Navy. In just over two hours, the scrappy, aggressive Taffy fleet sent the Japanese packing.

Ring, 89, of Sauk City, Wis., was one of just 55 U.S. survivors of the battle who gathered Saturday on the flight deck of the USS Midway Museum to remember the more than 1,000 U.S. sailors and pilots who died in what historians call a David versus Goliath battle that David won.

“It was like going into a gunfight with a knife,” said Capt. F. Curtis Jones, commander of Naval Base San Diego, to the crowd of more than 600. “They fought for us, they fought for their lives and they fought for their shipmates.”

Ring was an 18-year-old sailor on the USS Gambier Bay when a Japanese ship blew a hole straight through the escort carrier, and it began to sink. He climbed to the hangar deck where he was badly injured by flying shrapnel, then leapt into the water and swam to a distant life raft. Fifty-four hours later, he and the dehydrated sailors with him who hadn’t succumbed to thirst, delirium, injuries or shark attacks were finally rescued.

Ring’s heroic survival tale was one of many shared Saturday after the 90-minute service, which included speeches, scripture, songs, a three-volley gun salute and a gift to survivors of handmade patriotic quilts. The service was one of the concluding events of the annual Taffy 3 veterans reunion, which included a visit to Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery and a Battle off Samar memorial wall on Harbor Drive.

Speaker James Zobel, an archivist with the General Douglas MacArthur Foundation, said the heroism of the outgunned Taffy 3 fleet kept the Japanese ships from entering Leyte Gulf and interfering with MacArthur’s long-promised invasion to liberate the Philippines.

In a fiery speech that drew cheers from the often-tearful veterans, Zobel said the Taffy 3 ships — known as “tin cans” because they weren’t armored for heavy battle — bested the superior Japanese force through sheer force of will.

Author Pam Kragen, U-T San Diego

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

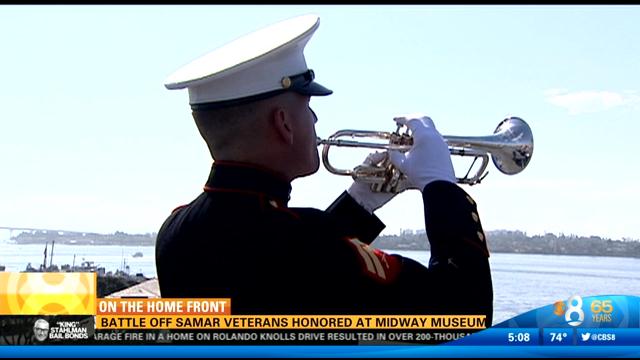

Battle off Samar Veterans Honored at Midway Museum

SAN DIEGO (CBS 8) – American heroes reunite at a special event on the USS Midway Museum. Forty-nine surviving veterans were honored for their service on the anniversary of the Battle off Samar.

It happened on October 25, 1944, in the Philippine Sea off Samar Island, a battle historians call “one of the greatest military mismatches in naval history.”

The 13 small ships of Taffy 3 were outnumbered by a Japanese naval fleet but they battled them anyway — for two hours — throwing everything they had at them, torpedoes, gunfire, planes.

“We were not meant to be a battle fleet, we did our best to stop them, or turn them delayed them,” one veteran said.

In the end, the Japanese retreated choosing not to invade the Philippines. Against all odds, Taffy 3 won but more than 1,000 men were killed or wounded.

“During the battle, I thought we were gonna die. We were right there, we were boxed in by the major Japanese fleet,” one veteran said.

The survivors of the Battle off Samar — now in their 90’s — received a special honor onboard the USS Midway Museum Saturday on the anniversary.

They came from all over the country. Alfred White is in town from Kansas.

“I don’t think during the course of the battle anyone had the time to be really scared,” White said. “The fact other people recognize this was something special we went through.”

They honor those who lost their lives that day. This ceremony, they say, even more special because they were able to experience it together.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Navy Years

Larry (2014)

Larry crossed the bar in October 2015

On December 7, 1941, my life, as well as the lives of most people in the world changed. The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, our largest naval base. President Roosevelt declared war on the Japanese and uttered his famous words, “This day shall live in infamy.”

At that time I was a junior at Mt. Angel College. In those days there was no doubt as to one’s duty. Patriotism was strong. Most everyone had a huge respect for our country and our government. It wasn’t long until I signed up in the Navy. After the recruiters evaluated my status, they determined I should finish my college degree and then go to Midshipmen Navy School to become an Ensign in the U.S. Navy. While I finished my 1-1/2 years of college, I was required to take some specific courses to prepare for the Midshipmen school. During this time I heard about all of the naval battles in the Pacific. I was anxious to get out there and “Give the Japs the hell they deserved.”

Mt. Angel College is located in Mt. Angel Oregon and was an accredited college operated in conjunction with Mt Angel Seminary. Many of our classes were composed of seminarians studying for the priesthood and day students like me. I was elected and served as Student Body President during my last school year ending June 1943. So between those duties, my expanded class schedules and my employment to pay tuition, I was kept busy to say the least. At our graduation I was elected class valedictorian. My folks were mighty proud of me and forgot all the rowdy things I had done as I was growing up. My employment during those years included many assorted jobs such as, picking strawberries and other berries, working in T.B. Ender’s service station and fix-it shop, peeling chitum bark trees, waiting on tables for the seminarians early breakfasts, washing their dishes, cleaning the college rest rooms, hoeing corn, picking hops, hoeing hops, training hops, working in canneries, hay bailing, picking onions, working in the Portland Post Office, and carpenter work in VanPort between Portland and Vancouver. I even helped the mortician, Ed Unger, a few times with his corpses.

My next older brother, Fritz, had already been put on active duty in the South Pacific. He was stationed on Guadalcanal and was mechanic on the plane of the famous navy pilot, Pappy Boyington. My oldest brother, Chuck, had joined the Merchant Marines. My next younger brother, Jeep, was in the navy as an instructor of recruits at the San Diego Naval Base. My younger brother, Bill, also joined the navy and was assigned to a CVE (escort air craft carrier). So my folks were proud of their five sons in the service. It was normal during the war to display a star in the window for each son or daughter in the service. My folks made sure everyone could see their five stars for their five sons.

After graduation, I was assigned to Columbia University in New York City for three months of intensive indoctrination and training in the Navy midshipman school. In fact the title given to us for this three month school was “The 90 day Wonders.” While attending Mt. Angel College I played in the orchestra, playing either the drums or French horn. At Columbia there was a band. I learned if you played in the band you didn’t have to do the extensive marching and drilling, so naturally I signed up to play the French horn.

Japanese Admiral Yamamota, Commander in Chief of Japan’s total fleet and Japan’s greatest naval strategist, had likened the U.S. to a “sleeping giant, that was vulnerable while slumbering, but once awakened, a terrible force to be reckoned with.” By 1943 the Giant was fully awake.

Needless to say, the 90 days were hectic and busy. We did get evening and weekend leaves and enjoyed the difference from our small town, Mt. Angel, to New York City. We did get to some dances and functions where we were able to meet some of the pretty N.Y. Irish lasses. We also got to see some of the era’s big bands at Radio City Music Hall.

After graduation from Columbia I was assigned to a “damage control” school in Philadelphia. It was there that I saw my first television in a store window. It was in its experimental stage in 1943. I got to see my brother, Jeep, at that time also. He was in training in Maryland. I was also able to visit Washington D.C. and see our national capital building. A great thrill.

I was assigned to the CVE aircraft carrier, “Gambier Bay, CVE #73. The carrier was being built in Keizer ship yards in Portland, Oregon and Vancouver, Washington. I was kept busy for several months learning all the information about our ship and getting ready to “outfit” and arrange for supplies and ammunition to be placed on board. We needed to go to Bremerton, Washington to take on bombs and torpedoes. We went down the Columbia to Astoria, where we steamed out into the Pacific Ocean during a storm. Our ballast was light so we pitched and bounced significantly on the way north to Bremerton. This was my first experience with a storm in the ocean. Just about everyone was sea sick on this trip. Many of them carried an empty can with them at all times. Luckily I had good sea legs and happily found out that I don’t get sea sick. This is a blessing, as its bad news to get sea sick. In fact, later on one of the fighter pilots on board was Larry’s Shore Leave in China chronically seasick. He told me he wished he was dead, his sickness was so bad. He begged and pleaded to go on every air mission, no matter how dangerous, to be able to get off the rolling ship. He was fine when he got in the air. Eventually he was transferred to a shore base.

From Pearl Harbor we ferried a load of fighter and torpedo planes to the Marshall Islands which had been invaded by our Marines and were in the final stages of a mop-up operation. Two of the main islands in the Marshalls are Enewetok and Kwajalein. We then went back to Pearl Harbor and took our squadron aboard to head for the next invasion which was the Marianas.

There was a major Japanese base called “Truk” which was west of the Marshalls. Our game plan was to bypass the major bases and then cut off their supply lines to render them ineffective. On the way to the Marianas we were attacked by Japanese torpedo planes. At that time my battle station was below decks in the bomb and torpedo compartment. I was ready to fight fires if they occurred. I realized that if there was a Japanese bomb or torpedo that hit that compartment, all of the bombs and torpedoes – with me in the middle – would go sky high. So I thought “what the heck”, I’ll just straddle one of the torpedoes during the battles. One Japanese torpedo plane did launch a torpedo that was set too deep to hit the bottom of our ship and it went directly under our ship exactly where I was sitting. It just was not my time to go.

We next traveled to San Diego where we took on our air squadron and headed for Pearl Harbor, doing training exercises all the way. The invasion of the Marianas was a critical battle. The Japanese knew that airstrips on Guam, Tinian and Saipan could send our B-52s directly to their homeland. They assembled all of their aircraft carriers to stop us at all costs. The battle turned out terrible for them, we called it the “Marianas Turkey Shoot”. We shot down over 400 of their planes, which included the cream of their 1st line pilots. We also sank most of their aircraft carriers. On the invasion of Guam, the Gambier Bay had the distinction of being the only aircraft carrier in history to use its 5-inch gun to bombard enemy positions on the beach.

From the Marianas we headed southwest to the Carolines and captured Ulithi in the Palau Islands. After we had captured the Palaus we were anchored in an atoll one stormy windy night. I was in charge of taking a whaleboat to a supply ship that was anchored across the bay. In the effort to stop attacks, there were no exposed lights allowed. I had a list of supplies to transport back to my ship. I was up on the deck next to a sailor from the supply ship. He was operating a winch and a boom to bring the supplies up from the hold of the ship. I could only see his outline. I was talking to him and I recognized his voice. He was Leo Traeger from Mt. Angel. I had gone to school with him. That’s a good small world story. His relatives still live in Mt. Angel. In fact, his daughter is married to Pete Grosjaques.

The next evening some of us were invited to be guests on an aircraft carrier from Great Britain. We had a fine British meal then did some fine drinking and singing with piano accompaniment. US ships did not allow alcohol, but the British did.

Also while in the Palaus I somehow became aware that my roommate from the Midshipman School at Columbia University in New York was on the Naval Seabees Base on Pellilu. I was able to find him and had a fine steak dinner at his base. I asked him how they were able to get such fine food. He said they had a truck that they would change names on. When a ship was unloading for the ranking officers they would put the right label on the truck and get in line, and as they were traveling back from the ship, in line with the other trucks, they would branch off and head to their base. My roommate was a genius. At Columbia he would never study, always reading fiction books instead, and ended up being graded as #3 out of a class of 800. After studying day and night I ended up as #60.

From the Palaus we steered for Hollandia, New Guinea, and then to Manus Island. Manus as the staging area for the big landing at Leyte Gulf in the Philippines.

While there I received a message from a destroyer that was also anchored at Manus. The message was from a friend of mine, Virgil Gooley. Virgil was the gunnery officer on his destroyer. We got together and had a great visit. We are still friends. He lives in Mt. Angel and is one of our Memorial Day Parade marchers.

The US task force of 800 ships to the Philippines was awesome. Ships were visible in all directions for as far as the eye could see.

By this time I had been promoted to Lieutenant (junior grade) rank and had been assigned to 4-hour watches as Officer of the Deck. In other words, unless the Captain was on the upper bridge I would be in full charge of our aircraft carrier. While I was on the bridge I would throw out “what ifs” as part of training. For example: We sight a torpedo coming in at 20 degrees to starboard – what do you do?

We invaded the Philippines at Leyte Gulf on October 21, 1944. General MacArthur, one of our greatest warriors, waded ashore and said, “I have returned”. He had said, “I will return” at the first part of the war when he was forced to retreat to Australia and to Hollandia, New Guinea.

The greatest sea battle of history was about to happen. On some of the following pages there are some technical reports of this greatest sea battle.

The night before the Gambier Bay’s part of this battle saw me on the bridge running the ship as Officer of the Deck. I had the 12 to 4 a.m. watch, known as the mid-watch. When scheduled for that watch I usually did not go to sleep until after eating breakfast at 4 a.m.

So, at 6 a.m. on October 25, 1944, I had not slept for 22 hours. On the 12 – 4 mid-watch things were calm. There was an US PBY plane that flew over us around 3 a.m. This had startled us some. I felt elated at the young age of 23, and with only 10 months of sea duty, that I was fully in charge and running this fighting machine, a USA aircraft carrier.

At around 6 a.m., I was still not in the sack when General Quarters was sounded. My battle station for General Quarters was Assistant Officer of the Deck on the command bridge. Also on the bridge were the Captain, the Navigator and the Officer of the Deck, so I was 4th in command on the bridge. I arrived at my battle station and was told about the huge Japanese task force being led by the largest battleship in the world, the Yamato. They were on the horizon and heading for us. It was not long until the Yamato used its 18-inch guns to attack us. Each shell that hit us or came near us showed a different color. Each of the Japanese battleships or cruisers had their own color – red, blue, purple or green. This would show each ships crew where they needed to make adjustments. We ended up getting hit 31 times before we abandoned ship.

A rope was let loose from the bridge to go down to the water level. When I got about halfway down there was a sailor who had emotionally frozen and would not go any further. I gave him a boot and got him to move on. As soon as I entered the water I swam as fast as I could to get away from the awful suction of the big ship going down.

The rafts were not very “deluxe” and there was only room inside the ring for the wounded. So the rest of us on my raft hung onto the sides. Sharks would appear at various times. A young sailor in my division had both of his legs torn off. After a day night or more some people started going insane. Some would swim away, some would drink saltwater as we had no fresh water supply and only a few cans of Spam to eat. We had sulpha and morphine for the wounded. The ranking officer on my raft went out of his mind. I got him down in the bottom of the raft and hit him so hard with face blows that I knocked him out. After that he was quiet, the important part is that he survived. For years after the war he would call and write me to thank me for what he claimed had saved his life.

After 44 hours in the water, just before daylight, we saw the outline of a ship against the light of the moon. We did not know if the ship was Japanese or one of ours. We were

so desperate we had to take the chance. We fired off a flare gun. The ship came alongside of us, we said hello and a sailor with a big southern drawl said, “How you all doing down there?”

One of our sailors still had a sense of humor. He said, “Well, if he is from Japan its from the southern part of Japan.”

The small ship was called an LCI. It had been 44 hours since we had sunk and 68 hours since I had slept onboard the Gambier Bay.

From there we were transported to Hollandia, New Guinea, where we boarded the Lurline, a Matson ocean liner. From there we steamed to Australia for a few days of R &R, and then on a straight line with no escort to San Francisco. They claimed the ship was so fast that the Japanese subs were not much danger. From San Francisco we were given some leave to go home.

Warriors coming home from battle were treated extremely well on the home front. Everyone was anxious to treat you well and hear about how the war was going.

After my leave I was assigned to a newly built aircraft carrier called Kula Gulf. Another small world story is that another friend of mine from Mt. Angel was also assigned to the Kula Gulf. It was Francis “Scratch” Hauth. We stayed good friends until he died some years ago. Scratch and I both owned the Abiqua cabin “Pack Rat Inn”.

Not long after I was assigned to the Kula Gulf I was appointed to the rank of full Lieutenant. The Captain said if I had a few more grey hairs I could have gone to Lt. Commander. It was on the Kula Gulf that a lot of poker was played. At least until the executive officer inspected our poker room and saw what he termed a “boars nest”. It was littered with cigarette butts and debris showing we were more interested in poker and fighting the war than we were with cleaning rooms. The result of that inspection was that all cards and chips were thrown overboard. It was quite awhile before we eased into another 24-hour poker game. Poker treated me fairly well. I sent enough money home to get into the building business.

One of our cruises took us to Guadalcanal, where my brother Fritz had been stationed as one of Pappy Boyington’s aircraft mechanics. Pappy was one of the war’s most publicized fighter aces. Unfortunately Fritz had been transferred to another island just before we arrived.

The Kula Gulf spent the last part of the war in the North Pacific until Japan surrendered. We did run into a super bad typhoon with winds of 150 miles per hour. We had to head straight into the wind all the way through the eye of the storm. It was a terrible storm. I was Officer of the Deck and running the ship on the mid-watch at the peak of the storm. The waves were so high that when we were in the trough of the water I could, from high on the aircraft carrier bridge, look straight out at a wall of water below the top of the wave.

There were two destroyers in our vicinity that rolled over and not a single sailor from the 500 was saved.

The storm damaged the front of our flight deck so severely that it folded back the total leading edge of the flight deck. We had to go back to Alameda to have repairs done.

After the war’s end we spent some time at SingTow and Tientsin China, Panama City and finally mothballed the Kula Gulf in Boston. Five Epping Brother’s Serve in WWII.

* * * * *

Presidential Unit Citation – Lawrence Epping

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Presidential Unit Citation to : Task Unit Seventy Seven point Four Point Three consisting of the U.S.S. Fanshaw Bay and VC 68, U.S.S. Gambier Bay and VC 10, U.S.S. Kilinin Bay and VC3 U.S.S. Kitkun Bay and VC 5 U.S.S. Saint Lo and VC 65 U.S.S. White Plains and VC 4 U.S.S. Hoel, U.S.S. Johnson, U.S.S. Heerman, U.S.S. Samuel B. Roberts, U.S.S. Raymond, U.S.S. Dennis and U.S.S. John C. Butler for service set forth in the following:

CITATION: “For extraordinary heroism in action against powerful units of the Japanese Fleet during the Battle off Samar, Philippines, October 25, 1944. Silhouetted against the dawn as the Central Japanese Force steamed through San Bernardino Strait toward Leyte Gulf, Task Unit 77.4.3 was suddenly taken under attack by hostile cruisers on its port hand, destroyers on the starboard and battleships from the rear. Quickly laying down a heavy smoke screen, the gallant ships of the Task Unit waged battle fiercely against the superior speed and fire power of the advancing enemy, swiftly launching and rearming aircraft and violently zigzagging in protection of vessels stricken by hostile armor piercing shells, antipersonnel projectiles and suicide bombers. With on carrier of the group sunk, others badly damaged and squadron aircraft courageously coordinating in the attacks by making dry runs over the enemy Fleet as the Japanese relentlessly closed in for the kill, two of the Unit’s valiant destroyers and one destroyer escort charged the battleships point blank and expending their last torpedoes in desperate defense of the entire group, went down under the enemy’s heavy shells as a climax to two and one half hours of sustained and furious combat. The courageous determination and the superb teamwork of the officers and men who fought the embarked planes and who manned the ships of task Unit 77.4.3 were instrumental in effecting the retirement of a hostile force threatening our Leyte invasion operation and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

For the President, James Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Oral True Account by Perry Anderson

About his Narrow Escape from Death in WWII (1995)

When my draft notice was received I was only 20 years old at the time. I had no idea what the future held in store for me. The bus took me from DeRidder to Fort Hamburg, Shreveport, Louisiana where I had to process for induction into service. I was given a choice of Army, Marines or the Navy. At first I joined the line for the Marines and then decided to step into the line to join the Navy as I though it would be the better choice.

On 28 April 1943 I was sent to boot camp at San Diego Training Station in California. Then I was sent to Seattle Naval Station in the state of Washington where I was to await further assignment in the service.

In Astoria, Oregon I joined the VC10 Squadron which trained up and down the West Coast. I was assigned to the ship, an escort carrier of the U. S. Navy, the USS Gambier Bay which I boarded in San Diego. My ship assignment was in V-2 Division, as an aircraft yeoman. My duties were to service the planes such as the fuselage and motor and make reports to pilots.

My first battle was at the Mariana’s. Guam and Saipan had already been taken from the U.S. When close to the Philippines, each ship had an escort in case a pilot went down in the waters patrolled by Japanese submarines. I was in the battles of Saipan, Tinian, Guam, and Battle of Lyte Gulf where the Gambier Bay was sunk on 25 Oct 1944. The first hit was at 8:20 a.m. and until we sank, we were being hit every other minute. At 8:45 a.m. our ship was hit on both sides by enemy fire.

The order to “Abandon Ship” came at 8:50 a.m. With shipmate’s dead or dying and many trapped on board, it was a heart wrenching sight to see when the order came to “Abandon.” That’s when we had to slide by ropes down the side of the ship into the water. All the while our hands were stinging and burning from the friction of the rope. Until I could locate a life boat, my life preserver kept me afloat. It was the style that was filled with milk weed kapok. When the strings were pulled, it inflated automatically. While abandoning the ship, the enemy ships in various directions were still firing at us. With men in the water and the USS Gambier Bay sinking, we did not lower our flag to surrender. That would have been disgraceful for our nation and our US Navy.

Our ship was sunk in the Battle off Samar after helping to turn back a much larger attacking Japanese surface. We had been ambushed by the largest Japanese Naval force ever brought together. Three of our escorts were also sunk. The U.S. aircraft carrier, USS Gambier Bay, in World War II, was the only one to be sunk by naval gunfire.

Though wounded in action (WIA), I managed to swim away from the sinking ship. I was one of the survivors on a donut life raft after spending 72 hours in water. It was designed for 72 men but because of decayed slats the raft had no bottom. Over a two day period, 1,110 men drifted more than 60 miles in shark infested waters without food or drinkable water. In the dead of night, with spotlights aglow in waters patrolled by enemy submarines, rescuers from Patrol and Landing Craft placed their own lives in danger to find and rescue the survivors still floating about at sea. We were in the South Pacific, near Somalia when what seemed like an eternity, a ship came by looking for survivors. Our exuberance turned to sadness when we were told the ship was already loaded but another ship would be by in about an hour. After not having food and water for many hours, I was too weak to climb the rope ladder when I was finally picked up by an LC1.

After being in water for such a long time, the first thing I did was to remove my clothes so as to dry them in the sun. About that time a Japanese plane flew over us so I had to do a quick change of covering my body with clothes. For many years that pair of pants were kept as a souvenir.

I was then taken to one of the Philippine Islands and put aboard a hospital ship. Then I was taken to New Guinea Naval Hospital. From there I was put on the luxury liner, SS Lurline and shipped to fleet hospital in San Francisco.

Seaman First Class (S1/C) Anderson was discharged 18 June 1945 in New Orleans. He was awarded five battle stars and a purple heart.

Perry crossed the bar in 1998

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

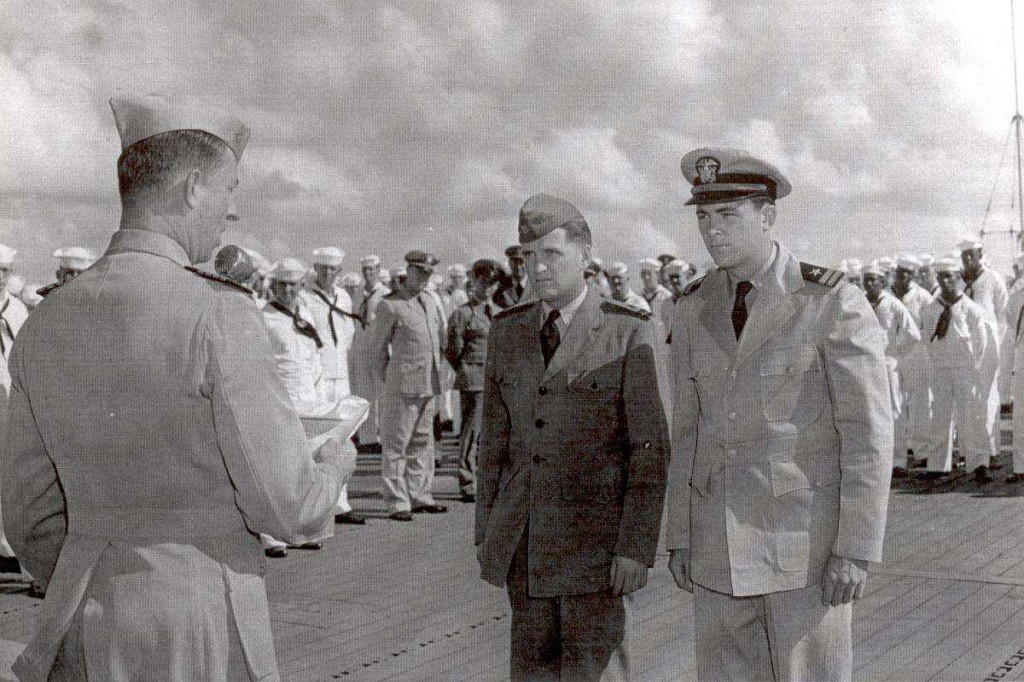

Crossing the Equator Ceremony

August 1944

Photos were provided by Damian Petro, great nephew of

Cmdr. James Sanders, Chief Engineer

James crossed the bar in February 1974

*

Our VF division was catapulted at 0500. We joined up and departed from over the lead destroyer. We arrived on station at about 0525, and patrolled from Point KING to Point NAN. At about 0800 over point KING a large bogie was reported. We started climbing at full military power as we were only at about 4000’. We had been chasing a bogie on the deck which turned out to be a TBM. We tally hoed three SALLY’s high above us (about 12000’), and Lt. Seitz and Ens. Dugan, his wingman overtook two of them to shoot them down a few miles west of Tacloban Town. I was unable to close within firing range. I think the third SALLY was also shot down by a VC-10 fighter. During the chase I became separated from my section leader, so I joined up on Lt. Seitz. We circled at point KING again until Lt. Seitz was forced to leave due to shortage of fuel. I remained on station as I still had about 65 gallons. At about 0840 a large bogie was reported coming in at point KING, high. Just then a large formation of twin-engine bombers was tally hoed. I was at 10,000’, and a I climbed to 13,000’. I sighted about 21 LILLY’s in close formation headed for Leyte Gulf a 15,000’. I made my first run on a section of LILLY’s, low, and on the starboard side of the formation. I fired a long burst at mid-range of about 200 yards at the section leader from a full deflection down to about 30 degrees. My tracers were hitting the starboard side of the fuselage just aft of the cockpit, but he seemed to suffer no serious damage. Then I concentrated my fire at his wingman at about 100 yards range. After a long burst from 20 degree deflection to almost dead astern, that went into his starboard engine and wing root, the LILY burst into flames, and dropped out of the formation. Just as he fell, in flames, his starboard wing came off. Just as the LILY burst into flames another FM-2 zoomed very close underneath me-coming from my left. He may have been firing at the same LILY as I although I saw no other tracers. There was no return fire from this plane, although the dorsal hatch was opened. He made no evasive action-but held in formation. His speed was 160-170 knots, and mine was from 180-200 IAS. I recovered to the right of the bombers and made another beam run from the starboard,this time on a lone LILY low and on the starboard side of the formation. I fired a long burst from full deflection down to about 30 degrees, and observed hits on the fuselage and cockpit. I then sucked in behind and fired another long burst at his port engine,which exploded and caught fire. Then I fired into his port wing roots, which also flamed. As the LILY dropped off on his left wing, I rolled to the left. As I did the rear hatch gunner scored 8 hits on my plane, although none did any serious damage. The LILY continued its roll and spun-in in flames. I recovered on the left side of the remaining bombers, and I now saw only six left. I made two more runs on the rear LILLY’s but observed no real damage from my fire. Three more of the bombers were shot down by other fighters, two were in flames, before they arrived over the transports in the Gulf. As the remaining three bombers dove thru the thin layers of clouds over the ships, the ships’ AA opened fire. I pulled out to the left and headed back to point NAN. I observed two planes crash into the water that had probably been hit by our AA fire, and one was close alongside a large landing ship just off shore. At Point NAN I joined up with Lt. Seitz, who had turned back, and Lt. (jg) Hunting. Aswe were all quite low on fuel we headed for our base. I landed aboard with from 8-10 gallons at 0930.