The Personal Account and Experience of

Joseph Solomon Brown

On the morning of October 25, 1944, we secured from general quarters. We were going to the mess hall for breakfast when the bell sounded and the announcement “All men man your battle stations” was given. Without breakfast, we all ran to where we were supposed to be. I went to the aft elevator pit. I was in charge of a fire detail.

We were getting hit from the big guns. We all heard the metallic click when the shells went off in the water. We knew it was just a matter of time before our ship would be hit.

I went to the fire hose, unwrapped the hose, and put the valve on. No water was coming out. I walked over to the Lt. to see what else I could do.

We received a hit on the fantail and I went down. The Lt. was decapitated and I was hit in my left leg. For some reason, I pushed my butt up and I was hit again. Someone yelled that Brownie was hit. Two guys came running with the wire stretcher. I did not want to go to the sick bay as it was by the gasoline storage area. I yelled and ranted until they drooped me and I crawled over to the sponson.

When the order to abandon ship was given, I somehow crawled over and jumped or fell into the ocean without a life preserver. God must have been looking after me. Someone from the flight deck threw me a life preserver circle and I sat in it until I was picked up. For some crazy reason I paddled over to another group when I felt a large fish pass me. When I got to the other group, two of the group were pulled down by sharks.

I met a buddy of mine on the second day. At dusk, we both saw a large tree that looked like a telephone pole. Prokop said to me, “Brownie, lets take this into shore.” which we saw the out line of. For some reason I stayed with the group. We never saw him again.

On the morning of the third day, before sun up, we saw small ships coming toward us. We thought they were Japanese, but thank God they were not. Someone put on a search light and said, “Hang on we will be back.” I wasn’t going to wait. I paddled to the small boat and started banging on the side with my fist. They brought me on board. Trying to play the hero I said, “I’m ok. All I want is water.” They let me go and I fell flat on my face. They gave me a cup of warm water and a shot of morphine. I did not remember anything for two days.

When we pulled in to Leyte Gulf, I was transferred to an LST hospital ship. From there to the US Comfort, a hospital ship, where I was operated on.

Joseph Solomon Brown

USS Gambier Bay CVE 73

Joseph crossed the bar in October 2009

In memory of Joseph and Gloria (Gloria passed in February 2011). Joseph’s personal account and experience is reprinted with permission from Joseph and Gloria’s children, sons Lynn, David, Gary, and daughter Jan.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Personal Experience and Account of Charles G. Heinl

1944 – 1946

(Air Department)

On January 4th, 1944, only 4 days before my 18th birthday, I took my oath into the U S Navy.

On January 13, I reported for boot camp at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station (Company # 107, 12th Regiment, 13th Battalion) along with a group from Ohio, Georgia and Tennessee. Many of these men were only seventeen years old. I was interested in something in the electronics field, but at this time the fields were very limited and most of the rates were frozen.

I completed boot training on March 9, and then I went home on boot leave and reported back to Great Lakes on March 18. At this time there was a large group of men placed on a troop train and headed for California, arriving there on March 22, at Camp Shoemaker.

After about two weeks of doing nothing, we went on another train to the US Naval Base at San Diego, California. At that time we were assigned to the receiving center at Balboa Park. After several weeks most of this group was assigned to the Jeep Carriers, and I was assigned to the USS Gambier Bay CVE-73. While aboard ship, I was assigned to the V- I division as an Airedale on the flight deck.

On May 1, we pulled out of San Diego for overseas duty. We arrived at Pearl Harbor on May 9 and anchored right next to where the Arizona had been sunk. You could see the oil coming up to the surface. I only had one liberty at Honolulu. It was not a very good one as they had an air raid drill and it took me away from my leisure.

On June 1st, we departed Hawaii for the Marianas Islands. I didn’t know this until after the ship departed. We were bound for Saipan with a stopover in the Marshall’s. (D-Day was scheduled for the 15th of June.) We were part of task force 58, and had countless General Quarters and were involved in the turkey shoot.

About August 2 we went to Eniwetok in the Marshall’s for more supplies and returned to the Marianas Islands. This time it was back to Guam and Tinian.

Next, we went to Espiritos Santos in the New Hebrides crossing the international date line and equator simultaneously.

On August 13, 1944, we were initiated into the Royal Order of the Shellbacks and toured some of the Solomon Islands, Guadalcanal, Tulagi & Florida Islands and a beer party.

Now it was back to the war. We were now part of Task Unit 32 and assisted in striking the Palaus, Yap and Ulithi.

The date was now September 20. We then went to Hollandia New Guinea for more supplies crossing the equator for the second time and then to Manus for an assembly of one of the largest fleets ever assembled. This area had a plateau of about ten to twelve miles long and about six to eight miles wide. We were waiting for the departure for the invasion of the Philippines.

We departed Manus, on about October 7, bound for somewhere in the Philippines. We did not know that we were going to strike Leyte.

On October 23 there had been typhoon warnings. And On October 24, as I did many nights, I would take a blanket from my bunk and sack out on the fantail of the ship as our sleeping quarters were just too warm. At about midnight there was a loud thud. I was told the next day the tossing of the ship had let one of our tractors drop down to the elevator on the hanger deck.

At Leyte, the US S Gambier Bay, was a part of Taffy 3 (Task Group 77.4.3) which was one of the 13 ships 6 CVE’S, 4 DE’s and 3 DD’s. Two other groups,77.4.2 and 77.4.1 ,were almost identical to this. Taffy I and III were 60 miles apart while 77.4.2 was in the middle.

GENERAL QUARTERS 0415 GQ

SECURED 0638 – A call to General Quarters was not unusual occupancy for those on the Gambier Bay as this was a daily duty.

SECOND GENERAL QUARTERS 0647 – As the Gambier Bay cruised on station the morning of Wednesday October 25, 1944, the pilot of one of the scout planes flying ahead of her radioed a startling message, “ENEMY SURFACE OF FOUR BATTLESHIPS, SEVEN CRUISERS, AND ELEVEN DESTROYERS SIGHTED TWENTY MILES NORTHWEST OF YOUR TASK GROUP AND CLOSING IN ON YOU AT THIRTY KNOTS.” It was a crack Japanese fleet steaming south at top speed to attack the Allied landing force at Leyte.

Leading that enemy fleet was the world’s largest battleship ever built for that time, the monstrous Yamato. She was big! Her main battery was nine 18.1 inch guns, thirteen percent bigger than any US Navy gun. Each gun delivered a shell weighing 3,200 pounds at a range of over seventeen miles. The Yamato’s speed was more than 30 knots. Nearly 10 knots faster than the tiny Gambier Bay. The Japanese and the Americans sighted each other’s ships at almost the same moment.

At 0659 the mighty Yamato opened fired. It was the first and last time she ever fired her giant guns in combat.

At 0807, the final hour of the Gambier Bay arrived. The IJN (Japanese) after firing for one hour and eleven minutes finally scored their first hit, as the ships action reports states. Whenever they would fire at us we would turn toward the salvos and the Japanese would try to correct their error and miss again. While doing this, all the US ships were laying down a smoke screen.

At 0810, after firing at the Gambier Bay for one hour and eleven minutes, the Yamato finally scored her first hits on the aft end of the flight deck and hanger deck on the starboard side. Fires broke out. Damage control did what they could. The shelling increased and casualties mounted rapidly. A large Japanese cruiser (Chikuma) closed to point-blank, a mere 2,000 yards away, and pumped 8-inch shells into the Gambier Bay’s thin hull.

At 0820, her battle report notes, “A hit in the forward (port) engine room below the water line.” The crew struggled against the seas, but within five minutes the engine room was flooded up to its burners and they had to be secured. Speed dropped to deadly seven knots. Damage mounted.

At 0837, the forward main steering control was lost as the carriers island, the tower of central control, took hit after hit. At this time we had two fatalities on our catwalk, Henry Stanley Klotkowski of Detroit, Michigan and Junior Williams from West Virginia. Junior’s father had lost two sons in the European War and he was going to be sent home by request of the American Red Cross after this operation.

0840 Radar Dead

0845 Gambier Bay Dead in the Water. One of the aircrewman that left the ship in a TBM talked to his pilot and said they are shooting at us in Technicolor, (Coral, Lemon & Lime) which produced dye color splashes. They used this method since they did not have radar control weapons at this time.

0850 ‘Order to Abandon Ship’ was given. As we had lost our power, some never heard it. I walked from Port side uphill ( The ship was listing to the Starboard side.) so that I could leave the ship from the high side. Joe Kimball from Kentucky and I cut down a life raft on the Starboard side right by the forward stack which was still smoking from the smoke screen. We exited the ship going down the rope.

When I got to the water, I shed my battle helmet and my flight deck shoes. Some of those who jumped off from a high position with their helmet on, could have killed themselves. The survivors swam away from the ship. Away from the concussions caused by explosions within the hull as it settled into the sea. The raft we cut free was full and gone so I went with the next group as they went by. I did not have a life jacket for the first day.

As we watched back we saw the ship roll over on its hull and begin to sink bow first exposing the screws. It then sank. Time was now 0907 according to the records. (The ship was sunk close to the Philippine trench, one of the deepest parts of the Pacific Ocean. It’s approximately 35,000 feet deep.)

The next two days I would spend with Commander Buzz (Fred) Borries the Air Officer, Chaplain Verner Carlsen, Chief Joseph Russell, Lt. Wm. McClendon LSO officer, Virgil Fitch, Ronnie Odum, and Loren Flood, only to name a few that I can remember. Those were the people that I spent two days and two nights with while I adrift at sea in shark infested waters. Earl Fetkenhier was using a one man rubber liferaft. He had a bad injury to his foot. He was also a boot camp buddy of mine from the V- 1 division. Someone placed him in this lifecraft as we didn’t want any unwelcome guests (Sharks drawn by blood). Daniel Martindale hallucinated and was going to take Earl Fetkenhier to a hospital. While adrift, one of the Japanese ships went by us taking movies, I thought they were going to strafe us.

Chaplain Verner Carlsen at some time early after abandon ship prayed the Lord’s prayer in unison.

Buzz (Fred) Borries took charge of our rations distributing the small pieces of spam, and malted milk tablets. The water was contaminated with salt water when the raft hit the water.

The swells were about six to eight feet, you would think the waves would go right over the top of you, because you are very buoyant in salt water. We would take turns hanging on to the life raft. I took my knife and cut off about six or eight inches of my trousers and slipped it on my forehead as it was very hot. The Philippines is at a latitude about the same as Central America, hot during the day and cold during the night.

The men began seeing sharks and I thought I saw them too. The sharks did get somebody right next to me and I never did get his name, this can yet be verified by Chaplain Verner Carlsen. As time went by the sharks became a real menace. You could see the dorsal fins in the water.

The first night, we saw a ship and we were real quiet as we thought that it was an enemy ship (Japanese).

Six hours, forty-one minutes after the Gambier Bay had been left in a sinking condition the first order was issued to conduct a search and rescue mission. The destroyer escorts were ordered to the scene. The spot they were directed to 11- 1 5 north 126-30 east. The second incorrect position. The delay of nearly seven hours between the time the crew abandoned ship and the time of the first order to send rescue ships is attributed by Navy Historian Morrison and other writers to three problems.

PBY’s were busy picking up downed pilots, Kamikaze attacks, and the ships were too busy defending themselves. If we would see a plane we would put dye markers in the water and at night we would fire very pistols.

After you are in the water for a while the water would taste cool and fresh, but some of the men died from the salt water.

On the second day, Harry L. Perry gave me a kapok as he had two life jackets. I fell asleep in this kapok.

The men were beginning to hallucinate, I thought I was on the ships bridge a couple of times. Dan Martindale was going to take Earl Fetkenhier to a hospital for medical attention. Some of the men were going to one of the islands and some just disappeared. Staying awake at this point was very difficult. I don’t know how long I slept in the water. It could have been between 1 and 3 hours.

October 27, 1944, after about 45 hours, we were finally picked up by PC 623. The men of the rescue group said that they couldn’t get us out of the water fast enough as there were a lot of sharks in the area. Some of the men with serious injuries floated for a day or so, then drifted off into death. Sharks found some men, attacked and killed them. Limited medical supplies on the rafts helped some survive for a while.

No one knows how many men and officers of the Gambier Bay died at their battle stations, or how many were lost awaiting rescue. The final count: 23 known dead, 99 missing 160 wounded. Of 849, 727 or 85% lived through what was probably the most unequal battle of two ships ever. The tiny thin hulled baby carrier shot down by the world’s largest battleship.

I was given a bowl of tomato soup and a bunk on PC 623 and later that day we were under attack and with all the Ack Ack I never woke up. We were taken to Admiral Kinkaid’s AGC ship a communication ship at San Pedro Bay inside Leyte Gulf, the USS Wasatch AGC 9.

The USS GAMBIER BAY (CVE-73), a small escort carrier of WWII, was sunk in a dramatic battle by a tremendously powerful Japanese force intent on attacking the under protected landing craft at Leyte Gulf, in the Philippines. Those who lived through that deadly hour joke about their tragedy today.

On the USS Wasatch (AGC9), an Amphibious Force Flagship, we were informed that the USS St Lo (CVE63) was hit by a Kamikaze around 11OO hours and sank. Sometime after this I was informed that two of the killed were from Coldwater, Ohio. They were F2/c William Bettinger, son of Mr. & Mrs. Arthur Bettinger and S2/c Paul A Buschur, son of Mr. and Mrs. Steven Buschur. Both were only 18 years old in April of that year. A Total 1,150 survivors were picked up from the largest Naval Battle ever fought.

Our group was placed on LST-617 bound for Hollandia, New Guinea and arrived there on November 10. We were placed on the SS Lurline for return to the United States via Brisbane, Australia.

Somewhere between October 28 and November 12, I had surgery under my left armpit and my chest for removal of saltwater sores on the Red Cross hospital ship Comfort. We were around Leyte or around New Guinea.

Passing under the Golden Gate Bridge on December 1, 1944 and arriving at San Francisco Pier 1, the Waves were playing “California Here I Come.” I was given a thirty day survivors leave and spent Christmas at home. I later returned to Watsonville, California for duty with Carrier Aircraft Service Unit called CASU 64 and spent 9 months there.

On August 15 (VJ-Day) they asked the personnel who would like to be transferred. Although I liked Watsonville, California, I held up my hand, and I was then asked to report for a physical at the personnel office. They told me that I had no medical records. I said that they were lost on the Gambier Bay which would have been 10 months earlier.

In the years to follow, I was active as a co-founder in organizing the USS Gambier Bay & VC 1O Association, Incorporated in the State of Minnesota in the late sixties or early seventies, and transferred to Ohio around 1986-87.

Charlie crossed the bar in December 2011

Republished with the permission of the Heinl family

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Personal Experience and Account of Louis Vilmer, Jr.

(AIR CREWMAN VC-10)

When the second General Quarters of the morning was sounded, Pilot Shroyer, Gunner Britt and I, radioman Vilmer, were fortunate to occupy one of the two TBM Avengers that were prepared for the early morning anti-submarine hop. We had a full load of fuel and were armed with eight solid-head rockets and two 500 pound general purpose bombs with both contact and dept-charge fuses.

We were launched by catapult and as we cleared the flightdeck the first Japanese salvo landed in front of the Gambier Bay. One splash to Port and three to Starboard. We flew right between them. When we reached altitude, Skipper Huxtable was already there and gave us a hand signal to head to the Japanese Fleet on our own.

When we approached the enemy fleet, Shroyer picked a target and as we broke through the heavy overcast he fired the rockets and his 50 caliber wing guns. Britt fired the 50 caliber in the ball turret. Shroyer was unable to open the bomb bay doors with the control in the cockpit and as a result of his trying we were very low and he did not have the power to pull away quickly. We skimmed the water along side of much of the enemy battle line just a few feet from the ships. We were so low that I, as a radioman in the belly of the plane, had to look up to see the Japanese sailors on their ship’s deck.

Finally we regained power and were able to pull away and up to altitude. Shroyer informed me over the intercom that the bomb bay door control in the cockpit was not responding and asked me to try the one in the radio compartment. It worked. He told me that we would make another run and he would tell me when to open the bomb bay doors. Shroyer chose a target and made his run flying from the cruiser’s stern toward its bow. I opened the doors on his cue and when the bombs cleared he was able to close the doors with his control. I then observed the results through the bottom rear window and reported to Shroyer.

The bombs did not hit the cruiser directly. They hit just a few feet behind the stern and went off underwater – probably as dept charges. Fighter pilots following us in on the run reported that the cruiser slowed and lost steering.

At a Gambier Bay/VC10 reunion years later in Oklahoma City, Skipper Hustable and Shroyer asked me to recall the happenings of that fateful day. Hux surmised that the direction and momentum of the bombs carried them below the waterline to the most vulnerable part of the ship and that would explain why the Japanese Captain was puzzled by what appeared to be a torpedo hit when no launch by plane was observed and no US Submarines were present.

Lou crossed the bar in March 2012

Republished with the permission of the Vilmer family

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Veteran of the Week – Michael Towstik

Published in January 2001 in the Staten Island Advance Service History by Carla Barletto

Michael Towstik gave himself an unusual New Year’s present in 1942: He enlisted in the Navy shortly after January 1, 1942, which also happened to be his birthday.

After training in Green Bay, Wisc., and the Chicago Navy Pier, he graduated as a first-class machinist mate and was shipped to the West Coast, where he went through Naval Aerial Gunnery Training. His training was interrupted when he broke two vertebrates in his neck while training on a trampoline, forcing him to spend two weeks in the Oak Harbor Naval Hospital, after which he received even more training in gunnery and radar training.

He was eventually placed in the VC-10 Squadron as a flight mechanic, and assigned to the escort carrier USS Gambier Bay in time to sail to Pearl Harbor. “We were docked next to the sunken Arizona, although we did not know it when we got there,” recalled Towstik.

While there the crew prepared to take part in the invasion of Saipan and Tinian islands. For his part, Towstik was assigned to the engineering mechanics crew. In 1943, after participating in the battles for Saipan, Tinian and the Pelau Islands, battles, the Gambier Gay took part in the fight for the Pelau Islands, then prepared for the invasion of Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. During that invasion, on Oct. 25, 1944, the Gambier Bay was sunk. Towstik was honorably discharged from the Navy in 1946 as an aviation machinist’s mate first class.

Awards and Honors

Towstik is a past trustee and delegate, as well as a current member of the Richmond County Post, Veterans of Foreign Wars. He was elected to the position of post commander in 1981. In 1983, the post honored Towstik with its annual Michael F. DiSogra Memorial Award for his service in veterans’ affairs. He is also a member of the Boy Scouts of America, the National Rifle Association, the New York State Rifle and Pistol Association; the CV Association and the Tailhook Association. In December 1975, he was awarded the Purple Heart by the Navy, 32 years after he should have received it for injuries suffered during the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Civilian Life

The soon-to-be 80 year old was born in Brooklyn and moved to Elm Park as a child.

Following the war, he tried a few jobs, and after a short stint in California, he returned to New York. Towstik then worked in various jobs with dredging companies, a copperworks factory in New Jersey and with the Bayonne Navy Yard as a wharf/dock builder.

He also joined for the Department of Sanitation, working on its tugboats. When that division was abolished, he became a housing inspector. He retired in 1983. His wife of 47 years, the former Avis Morrison, died in 1993. Towstik has two sons: Andrew, who is involved with computer maintenance, and Russell, who is in construction in North Carolina. He also boasts a grandson.

Most Vivid Service Memory

During the battle of Leyte Gulf, Towstik remembers it being quiet at first. “The ship was on submarine detail, and all precautions were taken … but mechanics had a lot of work to do; maintenance is always a problem.”

He and a partner had just fixed a plane and put it on the elevator when a tow tractor damaged its propeller. Since they stayed up until 3 a.m. fixing it, they vowed not to get up for “hell or high water” the next day.

Around 8 a.m., Towstik heard shells and explosions on the ship. “I went up to the flight deck with my partner. I was just wearing pants, I didn’t even have my shoes.” They found the ship under attack from Japanese planes. According to Towstik the ship took about 34 hits. “I looked around a saw an officer put down his ear phones, that was when I knew it was time to abandon ship,” he said.

After witnessing others jumping off the flight deck, some of whom hit other sailors or debris already in the water, Towstik decided on a different route to the sea.

“I went down a rope, with no knots, hand over hand because I didn’t want to get hit. I watched the officers throw over packages, I guess of coding information,” Towstik said. He estimates it took about 30 minutes for the ship to actually sink.

He had on a life preserver — a new one he had been issued only the day before — but got lucky and managed to climb into a floater net. A navigator told him they would hit land in about two days. All around him was chaos, destruction and death.

“We were getting hit with shrapnel and the garbage from the airplanes was all hitting us. That night a Japanese plane went over us, but all was calm.

“The next [evening] one of the fellas next to me gave a yelp. We figured he was injured, but instead [he was being attacked by sharks] and we had to cut him lose. We didn’t say anything and didn’t get his credentials, which I regret,” recalled Towstik.

The sharks kept attacking the crew in the water and wounded three more men. He remembers cutting all of the wounded loose and then having a peaceful night. “Finally, you could hear a wake in the water and somebody hollered out ‘How many are you?’ and somebody responded ’74.’ We were told that they would pick us up in a bit, but it actually took over an hour before we saw the light on the horizon,” he said.

Towstik and his crewmates swam toward the ship. “I got up to the second rung and fell back in. I got up again and they grabbed me. All I wanted was water,” he remembered.

After they were rescued, the men ended up aboard a medical transport that took them — during a typhoon — to New Guinea. Eventually, Towstik and the surviving crew members were put onto the Lurline cruise ship and were returned to the United States.

Republished with consent of Mike Towstik / January2015

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Personal Account of Douglas Koser

It was a Wednesday, no doubt about it. You may ask “how can you be so sure?” Well the breakfast menu on Wednesday was always the same, beans and cornbread. It never varied and after a while you might even get to like it. I was a 19 year old signalman assigned to the Gambier Bay CVE-73, a baby flat-top. The date was October 25, 1944. In only a few hours the Gambier Bay would be on the bottom of the Pacific, off the island of Samar, Philippines. My shipmates and I would be floating in the ocean for two days, praying for a rescue. My ship would have the dubious distinction of being the only carrier ever sunk by naval gunfire, commonly called surface to surface combat.

On that fateful Wednesday, breakfast was interrupted by the Boson’s shrill whistle, followed by the order “Attention all hands, General Quarters, man your battle stations.” The Japanese Navy had slipped through the unguarded San Bernardino Strait with a force of four battleships, eight cruisers and thirteen destroyers. Japanese Admiral Kurita thought he had come upon Halsey’s fast carrier group and he was ecstatic. If he could destroy them, his place of honor and distinction in history would be assured.

There were three groups of American ships assigned to the area just south and east of Samar. My group, code name “Taffy 3″ was in the northern most position, only 22 miles from the San Bernardino Strait when the Japanese were sighted. Their huge battleships, cruisers and destroyers dwarfed the Americans, not just in size but with their 18″ guns and ability to attain a speed of 40 knots. We had only one 5” gun on each of our six carriers, and as far as speed, only 22 knots. Taffy 3 came under fire and used smoke to camouflage, but shell after shell was directed at us, some with deadly accuracy. After merciless shelling causing irreparable damage, the Gambier Bay was dead in the water and the call came to “abandon ship.” The battle started at 6:45A.M. by 8:50 A.M., it was over.

The ship was listing badly to port as the crew prepared to abandon ship. There was utter confusion, men running all around me, some terribly wounded. I decided to jump on the starboard side, away from enemy fire. Somehow I found the courage to jump and after what seemed like an eternity I came up and gulped air into my lungs. I swam to a raft and hung onto the sides, the water was filled with men, kids like myself for the most part. The rafts were not the usual type, but had netting for a floor with a flotation rim, so we actually sat in the water, or hung onto the sides. The area was swarming with sharks and they took their toll. Besides the sharks there was the constant thirst and in spite of the warnings not to drink the salt water, some men did. The salt water caused them to see mirages and they had to be restrained to keep from leaving the raft and swimming to an imaginary oasis. Some did slip away as darkness fell and were never seen again.

We thought we would be picked up within a few hours, but the rescue operation force was in complete turmoil. For whatever reason the air search system was not put into effect. Finally on his own initiative, Rear Admiral Daniel Barby took control and formed a task group, consisting of two patrol boats – PC-623 and PC-lll9, along with five LCI’s.

Because of an earlier error in navigation, the rescue ships thought the survivors were 30 miles south of their actual position. Aboard PC-623 AI Levy was Officer in charge onthe Bridge. As night fell with no sign of survivors he decided to look elsewhere on a more northerly course. One of the rafts had been sending up flares every hour hoping to direct rescuers. About 10 P.M. a flare was spotted by Admiral Barbey’s rescue group. Al Levy aboard his PC-623 was sent to investigate, with trepidation. The lights from the flares could be Japanese. The men on the rafts could hear a ship approaching and they too feared the enemy. It was very dark, no sights just sounds. We held our breaths and silently prayed. Then it came, “Ahoy the raft” and the rescue ship’s lights were turned on us.

“We’re Americans” we shouted- “From the Gambier Bay.” Nothing could be more beautiful than the hull of that ship, as she slowed and lowered nets. We struggled to climb aboard but were so weak we needed help. The men of PC-623 reached down the netting grabbed us one by one and with mighty effort flung us over the side and onto the deck, like the catch of the day you might say. We wept and kissed the deck of the ship, others fell flat on their faces and passed out from exhaustion. We suffered from dehydration, sunburn and salt water sores, but we were alive. It was October 27th and the end of our two day ordeal in the water.

Florida 1998

I’m retired and living with my wife in Gulf Breeze, Florida, playing golf and enjoying each day. There are no visible scars from my Gambier Bay experience but I have an eerie feeling every October 25th.

On this particular morning the mailman delivered the usual bills and junk mail, but best of all my copy of “Old Shipmates”. This little magazine was the inspiration of shipmate Tony Potochniak. He worked hard locating as many old shipmates as possible, thus began the reunions that continue to this day. As I scanned my latest copy of “Old Shipmates” three familiar words caught my attention, they were “Gulf Breeze, Florida”. This article was dedicated to the memory of Al Levy, the man who with the other rescuers saved my life. I was saddened to hear had passed away only four months prior. To think he lived only five minutes away from me, and I never knew it. How I would have loved to shake his hand and say “thank you.” I looked in the telephone book to find his widow. Rose Marie Levy a gracious lady, listened to my story and was so pleased to hear from someone who knew Al. She invited us to her home and we reminisced for hours, talking mostly about AI and the wonderful man he was. She told me Al injured his shoulder as he repeatedly reached down to pull the survivors to safety, the pain was with him his entire life. He became a successful business man, philanthropist, writer, husband and Father. To me he was a hero.

Post Note

Ironically it was aboard an aircraft carrier, “The Enterprise” that I met my future wife. The date was October 25, 1945, one year to the day of the sinking. We were docked in New York harbor, it was Navy day and to celebrate visitors were allowed to tour the ship. I took it upon myself to show her around the ship and six months later we were married. We just celebrated our 53rd anniversary.

Douglas crossed the bar in January 2016

Published with the permission of the Koser family

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Personal Account and Experience of

Paul Bennett, Ensign

I joined the U. S. Navy in 1942 and served two tours with Composite Squadron 10 (VC 10), the first tour on the USS Gambier Bay (an aircraft carrier in Task Unit 77.4.3, commonly referred to as Taffy III) flying TBM torpedo bombers. My radioman or both tours was John W. Schrader, my usual gunner was Lee McDaniel (a member of the ship’s crew), although Murray A. Curtin was our gunner in Leyte Gulf. I went on inactive duty in 1946 with A Silver Star and an Air Medal. Later, Taffy III received a Presidential Unit Citation for Leyte Gulf activities.

When the war started I was working in Inglewood CA assembling the nose section for B25 bombers. You had to have been to college in order to be accepted for flight training in the Navy. I applied and just barely qualified. A year later the pressure for pilots was so great that anyone out of high school might quality. With a high school diploma and a year of flight training, anyone could be on a carrier in the Pacific. Our squadron had the skipper, a few 24 or 25 year olds, I was next at 22 years old in 1944, and we had a few guys as young as 19.

I finished basic flight training just after the battle for Midway. The Navy was short of torpedo pilots at that time because all the old TBD Devastator torpedo planes were shot down or retired after Midway. So all the pilots who got through training were assigned as torpedo pilots. All of my subsequent training was in TBM Avengers, which had replaced the TBDs. Future president George H. W. Bush was also a TBM pilot, and was in the class immediately ahead of mine.

I have only a few vivid recollections of WW II activities. One of these is following the skipper, Lt. Cdr E. J. Huxtable, back to the ship in early October 1945 after a mission to Tacloban. The skipper was flying a TBM. As we circled the ship to land, my radioman called me saying, “Look at the skipper”. We learned later that he was having engine problems. His plane, with the wheels down, was dangerously close to the water and his tail hook was skipping through the waves. His wheels hit the water and the plane was instantly upside down. A few minutes later, as we continued circling, all three crewmen were seen standing on the bottom of the wing of the upside down plane. Our plane guard destroyer promptly pulled up alongside of the wing tip and all three stepped aboard the destroyer. Later that evening the destroyer pulled up alongside the carrier, a line was shot across, and all three were back aboard. They joked that they were the only crew to ditch a plane in the ocean and not even get their feet wet.

There was a “welcome back“ party in the skipper’s room that night. When I left to go to bed about 10 PM it was still going strong. I and my crew were on standby when the first flight left the next morning shortly after dawn. Standby meant that we were suited up, in our plane, on deck, engine running, and ready to go instantly if one of those originally scheduled failed to launch for any reason. Everyone got off, the skipper leading this first flight, and we went back to the ready room. We sat around talking and the conversation centered on how tired the skipper looked. Bags under the eyes, etc. Someone said, “that old man is going to kill himself, he is 32 years old and still flying”. To really understand you need to know that most TBM pilots were very young. Early in the war our torpedo planes were very obsolete. Many were shot down. At the battle for Midway only one pilot survived out of one squadron, and he was shot down and spent days in the water before being picked up.

On another occasion, after flying missions to support a landing on another island, it may have been Peleliu, several of us were walking around on the beach waiting to get resupplied. Some army folks stopped us to ask if we had been flying support for them on the last island hit. We said yes. They said they would never do anything like that. I thought: here were guys who had been lying in the swamps full of snakes and bugs, in a foxhole with a friend, neither of you can move to relieve yourself for fear of the movement being seen by the enemy. Your only food is MRE’s and the water tastes funny. You look at the guy next to you and you see a bullet hole in his forehead.

I agreed that, as we flew around, a stray shell could hit us and we could be dead. However, after flying over several islands, with ships shooting at us, I only had one hole halfway to the wing tip on one wing of our airplane. We would go in fast, do our job, and not hang around sightseeing. Thus we were not real easy to hit.

This was the dawn of ground to air communication. I remember we’d get a request on the radio to strafe the north side of such and such a road with machine guns or rockets. We had to be very precise, because we knew the enemy was dug in on one side of the road, and our guys were on the other side. That’s how close the fighting was.

After landing back aboard the carrier, tired, sweaty, and so stiff from 3 to 5 hours strapped snugly in your seat, it was sometimes necessary for your crew chief to help you out of the plane. Then, after debriefing, you could take a shower, get into clean clothes, go to the snack bar for an ice cream cone, and if you wished go back to your room and stretch out on nice clean sheets. My thought was that I had it very soft compared to the guys on the ground.

The worst part was the boring long range recon flights. Sometimes if you were sick you just couldn’t help but go to the bathroom right in your flight clothes. The crew chief was very understanding if this happened. They would give you a fresh set of clothes and get rid of the dirty ones without making a big deal about it. It was all part of the job.

One other memory I have is how some of the pilots fooled the captain on the Gambier Bay. He didn’t want any of the planes to be painted with fancy nicknames and artwork like you see in pictures and in the movies. Our squardron skipper, E. J. Huxtable, however, didn’t see anything wrong with this and neither did some of the pilots. So they would paint only the left side of their planes, since that side couldn’t be seen by the captain in the tower on the right side of the deck. I think the best nickname was on the TBM flown by Pyzdrowski. Their plane was called “Petered Out and Pizzed Off.”

Another situation I remember was Leyte Gulf. Early on the 25th of October, 1944, there was a “general quarters” order on our carrier (the Gambier Bay) followed by a “pilots man your planes”. Shells from battleships 20 miles away were splashing down around the ship. With planes full of gasoline on the deck any leak could have been catastrophic. When I got to the deck, planes were being launched as fast as possible. There was a TBM near the back of the ship with no pilot. I got in and started down the deck toward the catapult. My radioman saw me and climbed in. We took off and John called me to say that the bomb bay was empty and there were no rockets under the wings. All we had were .50 caliber machine guns. Although there’s no way to confirm it, I have always felt that mine was the last plane off the deck before the ship went down.

Admiral Oldendorf and his battleship fleet had been sent south to stop a Japanese fleet coming in through Surigao Strait. It was thought that he might need help so overnight our planes had been loaded with the few torpedoes we had so they would be ready to leave at first light. The Japanese fleet was knocked out by Oldendorf and so we were not needed. So the deck crew started to reload the planes with bombs, in order to be ready to go back to Tacloban to help the army with their landing on Leyte. Rearming was incomplete, so most planes left the deck empty.

As we climbed out through a rainstorm I lost sight of our other planes. One of our fighters found me and pointed the way to the Japanese fleet. He was faster than us, so when we got to the enemy fleet there were no other planes in sight. We fired a few 50’s at cruisers and battleships. I decided that 50’s were doing no more than scratching the paint on armored ships. I pulled up into the clouds and, when I came out, I saw a flight of Taffy II planes heading south. I knew that there were other US carriers south of us so I followed and landed on the Manila Bay at about 10 AM. My radioman pointed out what looked like a 50 caliber hole in the right wing about half way out to the tip. We saw no other damage.

We were refueled, loaded with 4 500 lb bombs, and headed back north. Since I was not part of their squadron, I was tailend charley in the strike. We attacked a Japanese cruiser but the planes in front of me were missing the target with their bombs, because we were instructed to set our bomb releases for an interval so they would drop one at a time. When the plane ahead of me started his dive, I waited to get an interval so we did not collide over the target. As I started in I saw the splashes from his bombs, straddling the cruiser as it was turning. By this time I was in my dive, and I pulled the bomb release and the first bomb dropped. I saw that I would be about abeam when the bombs got to the target, so that my chances of a hit were almost nil. I then pulled the emergency bomb release and dumped all 3 remaining bombs at once on what we have assumed was the Japanese cruiser Suzuya. Although I couldn’t see it, my radioman and gunner both confirmed the hit. I then went south again and landed on the Fanshaw Bay, which was on its way out of the battle area. I learned later that our attack was successful: the Suzuya was abandoned at 1150, and at 1322 sank at 11°45.2′N 126°11.2′E

When we reached the island we were to stay at, there was a problem. There were no tugs and the Fanshaw Bay’s anchor had been shot away at Leyte. A new dock had just been completed at this island by the Sea Bees. The ship’s Captain positioned the carrier across the end of the dock and hoped for the onshore breeze to drift us over to the dock. It did. When we hit the dock the ship just kept moving and we wiped out about 20 feet of the new dock.

After we left the Gambier Bay, which sunk shortly after we took off, most of the squadron were directed to the air strip at Tacloban, where many of our planes were wrecked landing in the sand. The pilots were taken south to one of the other islands while waiting for a transport to return them to the States. When I joined them I was met with the statement “We thought you were dead”. Many of my squadron knew that I had taken off, but since I was never heard from again, I was assumed to have been shot down. Actually I was sailing around on two other carriers for a week or more.

For hitting that Japanese cruiser on the 25th, I was later awarded the Silver Star.

My citation reads as follows: “For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity as Pilot of a Torpedo Plane in Composite Squadron TEN, attached to the U.S.S. GAMBIER BAY, in action against enemy Japanese forces in the Battle off Samar, Philippine Islands, on October 25, 1944. Launched from his carrier without bombs while the vessel was under attack by enemy heavy surface forces, Lieutenant, Junior Grade (then Ensign) Bennett pressed home one strafing attack against a cruiser and one against a battleship despite intense antiaircraft fire. Landing on another carrier later than morning, he participated in a subsequent attack on the retiring force as part of a striking group from that ship and succeeded in scoring three bomb hits on a cruiser in the face of heavy fire. His outstanding airmanship, courage and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Paul crossed the bar in February 2012

Published with the permission of Andy Deveau, son-in-law of Paul Bennett

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

My Navy Experiences by Dean Moel

I am coming to San Diego. My daughter from San Antonio, Linda Shimerda is coming too. I went to Fredricksburg at their request on September 18-19, 2004 for the symposium. I was interviewed of my part and the VCR and DVD will remain in the Bush Room forever. After 60 years I have told more of my Navy life than ever before, Dick Pinch and I were interviewed at Cedar Bluff, Iowa, and have that DVD for my keeping.

Dick was a gunner on a 20mm right in front of the bridge. I was a trainer on a twin 40mm, the second tub from aft on Starboard quarter. In a nutshell, after we were dead in the water, before abandoning ship, Bob Allison, the Pointer on the other side of our 40mm, and I went in through our ammo room and heard “ABANDON SHIP.” We were going to cross the catwalk to the port side to jump on the low side but could not get across on account of fires. We went back in the ammo room and Bob said, “what are we going to do”? We sat down and I had a cigar and broke it in two and it up, yes, in the ammo room! We got up right away, went out to our gun. People were going over the knotted line, but that was too slow. I got my feet on the gun tub and jumped fee first. I did have presence of mind enough to remove my helmet. It was bad enough with my Kapok jacket to stretch my new two fee, felt like that anyway. I have maintained all my life, it was 60 feet to the water, what with the list to the port side, which was considerably the time I jumped.

I was a ships cook striker and traded two cans of canned turkey for a CO2 life belt, which I thought I just had to have. Immediately I swam aft and a lot of guys were already there and a red dye marker shell kit right there. One man said he didn’t’ have a life jacket, so I gave him the CO2. I don’t know who he was or if he survived, but I hope so. After the marker shell hit, I swam away to the Starboard as fast and far as I could. I didn’t see the Gambier Bay roll over but did see it go under. Then I really started to swim away until I felt the underwater explosions. I took off my Kapok and laid on top to keep the water out of my rear end. I kept swimming until I looked around and there were only three of us in sight, and by the sun it was around noon. Two guys showed up, Henry McGlaughlin, my friend from Des Moines, Iowa, and I recognized the other man but did not know his name.

Later on that afternoon three of them swam away to look for something, crew I suppose, two went together and one by himself. Only Henry and I were left, no one insight, nor anything else. We kept swimming and drifting until dusk, which probably was 10 p.m. One hell of a long day. Henry was starting to hallucinate and swam away from me. By this time it was getting pretty dark, and I watched him until he came close to something in the water. He came back and passed me. I don’t know how he was able to swim so fast, as we were so tired. I did manage to get him stopped and asked where he was going. He replied that there were a lot of Japs floating in the water. He sway away, never to be seen alive again. I was the last person to see him alive and give thought to him every day of my life, if only for a few seconds. I know none of his family know how he left this earth.

Decision time for me, all my myself, and 18 years old. It was getting darker and I had to do something quick. I thought if those Japs in the water, which they did scuttle a cruiser during the battle, they would either take me in, or kill me, or I will drown by myself. I decided to go to them and ask who they were and finally I heard 90 guys from our ship. Poor Henry was never heard of again.

Dick Pinch, Tom Clancy, both of the 1st Division and my very best friends were in the group. I was so tired from swimming all day, I started to drop my head in the water and sleep. Dick kept running his finder hard up under my chin, that hurts like hell, to keep me awake. I do remember seeing one man Jap subs by us, and couldn’t figure out why they did not pick us up. I was starting to hallucinate. Dick and Tom kept me awake all night and the next day and night until we were picked up. I stayed awake and afloat the rest of the time we were in the water. Dick and I kept a big red haired man afloat and alive untl we were picked out of the water. We were covered with oil, sun burned, my jaw bones were raw from rubbing on my life jacket. Anyhow, the crew of the L>C., that picked us out of the water, gave us all they had, bunks, blankets, which were ruined from oil and blood. This red haired guy was sitting between Dick and I eating tomato soup and crackers. This was the first food since chow the night before we sank. Red spilled his soup on me, and I started to cuss him and he fell over dead on me. At least he wasn’t wounded and suffering like Henry.

Then came the Jap torpedo plane and dropped that mile long torpedo in front of us. Dick and I didn’t even get up. “Let her come we said”. The skipper dodged it and took us in to Letey to a L>S.T. A doctor put our miracle drug penicillin powder on my face and raw jaw bones. I went down below and everyone not wounded was leaving. I told Dick the doctor wouldn’t let me go, he said, “ask him again”. I went top side and asked him if I could go with my buddies. He started swearing and said my face would rot and fall of and to stay the hell there. I went down below, told Dick and Tom I couldn’t go, they pulled me in between them and we walked off the L.S.T. We took another L.S.T. to Hollandia, New Guinea, the worst cruise the Navy ever gave us. Then we left for Brisbane, Australia, and got more penicillin and my face was pretty well healed before I returned home.

I could go on for another 500 pages of the experiences of my Navy life. Later I was assigned to the USS Pine Island, AV12, sea plane tender. We were in Buchner Bay at Okinawa when the war ended. From there I flew to Tokyo for the signing of the peace treaty, then onto China, and home on April 1, 1946.

Published with the permission of Dean Moel, February 2017

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Forrest Kohrt, Aurelia Veteran Recalls WWII Ship Sinking

Forrest Kohrt 86, is well-known in Cherokee County as the former County Extension Director – a post he held for 31 years until his retirement in 1985. What many people may not know is that the Rock Rapids native considers himself heaven-blessed to have even been around to hold that post.

In 1942, Kohrt and a group of other young men from the area traveled to Des Moines to enlist in the service, on the heels of the December 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor. Kohrt was a student at Iowa State at the time, but admits today that he really didn’t get into his studies much during the brief time he was at Ames, feeling it was more important to travel to Sioux City to visit his girlfriend Lois Follett, who was in nursing school there.

Kohrt was turned down when he first tried to enlist, because he told the examiners that his brother had asthma, even though he assured them that he did not have asthma himself. A short time later, they changed their minds and notified him that he had been accepted into the service.

Kohrt was initially stationed at the Naval base in San Diego, California, but was then reassigned to the Great Lakes Naval Base in Chicago for training. He studied aircraft mechanics and carburetors, and was assigned to the USS Yorkton. That ship was in dry-dock for repairs when he arrived in Astoria, Oregon, however, and he was reassigned to join the VC10 unit of the Navy Air Corps as a carburetor specialist, also stationed in Astoria. Kohrt and his new bride Lois (they were married in October 1941) enjoyed their time in Astoria, but soon the unit’s planes were loaded aboard the USS Gambier Bay, a small aircraft carrier, and the carrier shipped out in April 1944, headed for the Pacific theater of war.

Kohrt remembers that there were “between 800 and 1000” sailors aboard the Gambier Bay. The ship was used to ferry planes to Honolulu and the Marshall Islands, and entered into the battle of Sai Pan in the Marianas. They were also involved in a battle in Palau.

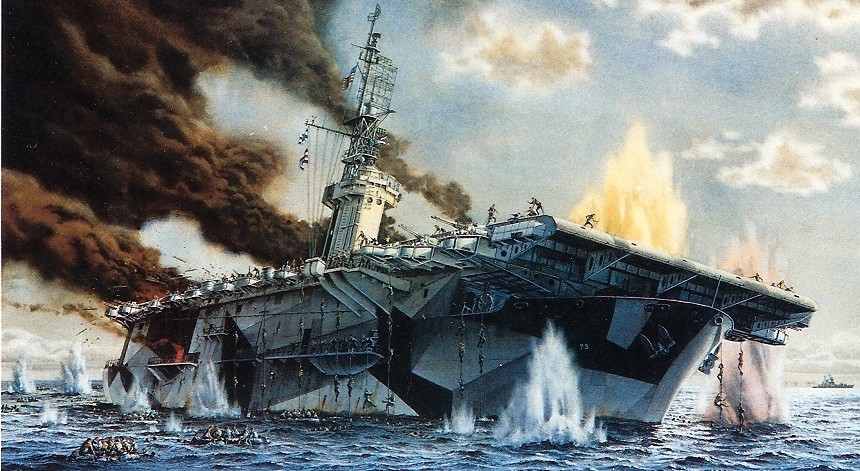

Sinking of The USS Gambier Bay – This portrait re-creates the sinking of the ship Forrest Kohrt and hundreds of other sailors were aboard when she was sunk in December 1944.

On a December morning in 1944, the Gambier Bay was involved in the second battle of the Philippine Sea, when they were struck by a shell from a Japanese ship. The shell took out the Gambier Bay’s steam supply, leaving the sailors “sitting ducks.” Forrest Kohrt said he was carrying a fellow sailor who had a piece of shrapnel in his lung to the ship’s sick bay, and was talking to a buddy outside the sick bay, when Kohrt was hit by a piece of shrapnel himself. The shrapnel went through Kohrt’s right arm, along an artery, and exited him, proceeding into the shoulder of the man to whom he was talking. One inch of bone in Kohrt’s arm was blown away by the shell.

Eighteen more shells hit the ship, sinking it to the bottom of the ocean – the only American ship in WWII which was sunk by surface-based weapons. An estimated 200 sailors were killed in the attack. The order was given to abandon ship, and the survivors, including Forrest Kohrt, were left to fend for themselves in the cold South Pacific Ocean.

Kohrt and three other sailors, including the man who had the shrapnel in his lung, hung on to a 4′ x 4′ piece of board. Kohrt had placed a flat piece of wood on his arm to try and immobilize it, but when he got in the water the piece of wood started floating, so he took the wood off. To try and keep the injured arm still, he opened up his belt, put his arm through the opening, and cinched up the belt.

While the four men were floating, they noticed an object which looked like a barrel floating near them. It was indeed a barrel – of fresh water. They also found a supply of malted milk tablets – a kind of an energy tablet – and Kohrt feels the tablets and fresh water saved the men’s lives. Three of the four survived, with the man who had incurred the shrapnel in his lung being a casualty.

One time, as they were out there o the ocean, Kohrt felt that one of the other survivors was bumping his injured arm, and was about to tell him to stop when he discovered what he was feeling was a shark’s fin. “Apparently, ” mused Kohrt, “he wasn’t hungry.”

After a time, Kohrt and his group got to a group of about 40 sailors who were hanging onto a cork net, and they joined that group. The next day, they spotted some ships coming towards them, and they figured the ships were picking up survivors. One of Kohrt’s group swam to the lead ship and asked to be picked up, but was not allowed on the ship for some reason. Later that night (the night of their second day out), the group were rescued – by a ship which, ironically, was skippered by Cherokee’s own Harlan Moen – although Kohrt and Moen didn’t piece that information together until several years later.

Moen’s ship took Kohrt and his shipmates to the hospital ship the USS Comfort, which took a detour to Sydney, Australia to pick up other casualties before returning to Oakland, California. Kohrt spent two weeks in the Navy hospital in Oakland, where the doctors got started on his arm, making sure it wasn’t infected. He was glad when his request to be transferred to the hospital at Great Lakes – much closer to home – was granted. In Chicago, Kohrt was unable to straighten his arm out, and a specialist from Seattle was brought in to operate. Though he says it’s a bit shorter than his left arm, and doesn’t always function as he’d like, the injury was treated as well as it could be, and he is fully functional.

Kohrt recuperated in the hospital in Chicago for close to a year. Lois and their young son Bill got an apartment in Chicago, and after a while, Forrest was able to spend weekends there. He was there on a visit, in fact, when he heard the news that the war had ended.

Forrest was discharged from the Navy in November 1945. He and his young family, which eventually grew to include two other sons and a daughter, settled initially in Rock Rapids. Lois worked in the hospital until the fall of 1946, when Forrest returned to studies at Iowa State, a much more mature man thanks to his family and the war-time experience. Kohrt received his Bachelor’s Degree in Animal Science in 1949, and started a career with Iowa State Extension, initially at Garner, then Knoxville. The family moved to a farm between Cherokee and Aurelia in 1955 when Forrest assumed his position as County Extension Director. Lois was actively involved in nursing at Sioux Valley Memorial Hospital, and the four children – Bill, Alan, Stan, and Cindy – attended and graduated from Aurelia High School.

After their retirement in 1985, Forest and Lois moved to a house in Aurelia to enjoy their retirement, and they did just that for twenty years, until Lois died in December 2005. Forrest still lives in the home in Aurelia, and is a regular at local coffee gatherings.

Of his war-time experience, Kohrt says he and his fellow sailors figured they would have to fight the enemy within the U.S. borders following the attack on Pearl Harbor. “We really didn’t know what to expect – didn’t know what it was like to be attacked.”

Kohrt has been a member of the American Legion for more than sixty years, and is proud of the “sixty-year pin” he received from the Legion. He has also been active in his church through the years, and strongly believes that “the Lord was there the whole time” during the sinking of his ship, the long two days in the water, and the year-long recuperation.

As we celebrate Veteran’s Day this week, we think of vets like Forrest Kohrt, who have been there throughout the years, doing what they had to do to keep the United States strong and free.

Published on Monday, November 12, 2007 in the Cherokee Chronicle Times, Iowa, by Dan Whitney, Staff Writer

Forrest Kohrt crossed the bar in June 2008

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

World War II Memoirs of Earl E. Bagley

An Idaho Landlubber at War with the Sea, the Sharks, and the Shells

Introduction

There are probably very few American your beyond 10 years of age who have not developed a resentment for phrases beginning with, “When I was”. It is just as natural for a man learning fatherhood to say, “When I was you age”, as it is for a baby learning to talk to say “dada”. Who has not heard from a parent, a brother, a sister, a teacher, or friend such declarations as “When I was in the first grade” or “When I was on the team”, “When I was struggling through the great depression”, “When I was manager”, “When I was in the Army”, etc., etc., etc. For some unexplainable reason, I have not resented the remark to the extent of vowing never to bore my children or family with such egotistical chatter.

The phrase is almost always used to draw attention to special virtues, sufferings or achievements of the narrator. Hence, for some 55 years, my wife and our descendants have endured, patiently or otherwise, the frequent use of it. Because of their indulgence I begrudge no man the right to use it, and encourage our offspring to make the most of it. To them, is this work dedicated. Now let me tell you about “When I was . . . .” in the US Naval Reserve. Some exaggeration is admitted but misrepresentation – – – never!

To continue to read Earl’s story, please click on each link below.

When It Was – by Earl E. Bagley – 1 of 4

When It Was – by Earl E. Bagley – 2 of 4

When It Was – by Earl E. Bagley – 3 of 4

When It Was – by Earl E. Bagley – 4 of 4